In 2015, Facebook launched its Free Basics app, offering a limited suite of Internet services for free in partnership with mobile network operators around the world.

This provoked widespread debate on whether Free Basics violated network neutrality principles that many believe (myself among them) are essential to maintaining the diverse and serendipitous nature of the Internet.

For me the answer was a paradox. While I believe in the importance of network neutrality, I also recognise that affordability can be a more difficult barrier to transcend than the most impervious firewall.

Lack of affordable access to the Internet may be the biggest network neutrality violation of all. Free Basics directly addresses the issue of affordability and deserves acknowledgement for that.

Looking further back, to 2010, when Facebook launched Facebook Zero, offering zero-rated access to its website, I applauded the company because it alone seemed to get the issue of affordability at the time.

I argued then and still believe that lowering the cost of getting online will allow people the freedom to discover what they value on the Internet and to create new value through their interactions with others.

Matt Ridley captures the essence of this in his book The Rational Optimist when he says:

Evidence suggests that cultural evolution depends on exchange and trade to bring together ideas in much the same way that genetic evolution depends on sex to spread genetic mutations, or in the case of bacteria, on horizontal gene transfer. When starved of access to a large “collective brain” by isolation from trade and exchange, people may experience not just less innovation, but even regress. The capacity for ideas to have sex on the Internet is likely to accelerate cultural evolution still further.

But that was 2010, and things have changed. Facebook’s growing dominance has led to a situation where new users coming online can mistake Facebook for the Internet. Concerns have grown that Facebook’s news algorithms are increasingly isolating us from diversity of opinions by showing us things we “like” to see. It is also at the centre of the “fake news” controversy, with widespread concern that its news and advertising system has been directly manipulated by external forces to influence public opinion.

There are also concerns about just how much personal information Facebook is capturing about its users and how that information is being used.

Problematic

Finally, Facebook is no longer just Facebook, it is also WhatsApp, Instagram and probably a host of promising Internet start-ups that you haven’t heard of yet.

Facebook is a privately held company with no transparency in its operations or behaviour on which most of us are conducting our public and private conversations. To say that all this is problematic would be the understatement of the decade.

Thus, any system which purports to be open, as Free Basics does, but in reality creates a strong default towards the Facebook platform is part of the above problem.

Perhaps you think that defaults are irrelevant, and the informed user can simply click away to something else? Research suggests otherwise. And if that weren’t bad enough, platforms like Facebook (although they are far from alone in this) are deliberately crafting engagement to hijack our attention and our choices.

Having spent much of my career advocating for affordable access, I find myself in a bit of a crisis of faith in what I am selling. I have gained so much from the Internet in terms of learning and social connection that I couldn’t conceive of my life without it and yet evidence that our very independence of thought is now potentially undermined by Internet platforms is deeply disturbing.

So, what to do? Tell the one billion unconnected people in the world that, nevermind, they’re better off without it? A part of me is tempted, but I am too much a believer in the social nature of our humanity and the potential that connectedness represents to give up on the Internet. The train may have gone off the rails, but that doesn’t mean we should scrap railroads. We need a better railroad.

That better railroad starts at the bottom of the pyramid. Free Basics is not what we want, but we don’t want to give up on affordability. Two years ago, I proposed a simple solution. Why not just zero-rate basic rate Internet for all mobile Internet devices? That would allow people to discover value in the Internet on their own terms and create inclusion where it is most challenging, at the bottom of the pyramid. After all, Facebook doesn’t pay mobile operators to offer Free Basics; they underwrite the costs themselves. For a mobile operator, why would you pay to entrench a digital giant?

Have you ever got one of those ideas that you just can’t let go of? You try and try to poke holes in it, to dismiss it as unrealistic, to forget about it, but it still keeps you awake at night. An idea that seems so blindingly obvious that you can’t help but wonder why it hasn’t happened already. That’s where I am with the notion of creating a universal, free, basic-rate Internet for all.

The article I wrote captured a modest amount of attention culminating in The Atlantic picking up the idea, followed by a modest flurry of social media activity and then nothing. I couldn’t see a way of moving forward and tried to put the idea to sleep but, like a colicky child, it would not rest and I would bend anyone’s ear who was prepared to listen.

Radically different

This led to a serendipitous conversation in Kampala in 2016 with Christoph Stork and Steve Esselaar of Research ICT Solutions, who I discovered were kindred spirits on this issue and had already been thinking along these lines themselves. Having found common cause, we began to make plans. We applied to the Mozilla Equal Rating Challenge and made it to the final round but didn’t win one of the top three prizes. Our proposal was radically different from the other contestants proposing community-led wireless projects. I can only imagine it must have seemed too far-fetched to the judges.

Undeterred, Christoph led the writing of a research paper which makes a stronger and more detailed case for Universal Basic Internet (UBI). The paper, entitled “Universal Basic Internet as a Freemium Business Model to Connect the Next Billion” has just been published in the DigiWorld Economic Journal. A conference preprint is available (PDF).

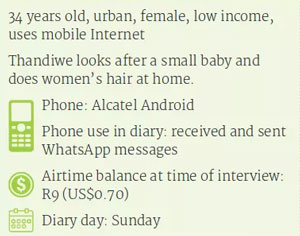

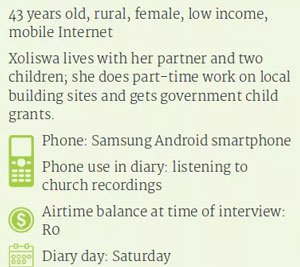

We continue to advocate with regulators and operators for UBI. I was inspired to write this article because of recently published research (PDF) by Indra de Lanerolle, Marion Walton and Alette Schoon, entitled “Izolo: mobile diaries of the less connected”. This work profiles the mobile usage of the least connected in South Africa. I can’t recommend this work enough as it gives unique insight into the lives of those whose access to communication is not as obvious or stable as statistics might imply. Here are a couple of users they profile:

Thandiwe spends about R12 (a little less than US$1) a month on data and most of the time she keeps the data off on her phone to avoid incurring data charges. She’s a hairdresser and coordinates with most of her clients on WhatsApp, but this must be carefully managed in order to conserve her data balance. Imagine if WhatsApp (or WeChat or Telegram or Signal or Viber or another messaging platform) were always on for her. Messaging services are an enabler of any home-based or informal business. Enabling UBI would be a business boost for everyone at the bottom of the economic pyramid, not to mention enabling the discovery of other kinds of value on the Internet. Reading the profiles of the various people in the report, it is easy to see that a disproportionate amount of time is spent by the poor coming up with strategies to affordably use the Internet. The necessity of these strategies takes up energy and time, but it also excludes the casual exploration and “play” on the Internet that leads to serendipity.

As a mother of two living in a rural area managing part-time local work, child support grants, Xoliswa fits my stereotype of black South African women who shoulder burdens that I find hard to imagine. Up before dawn, maintaining local livestock, feeding the family, finding work and generally keeping things together. For the poor, the logistics of organising work and family life is proportionately a much bigger burden than for the people even just a little higher up the economic ladder who have regular jobs and who can afford data services that don’t have to be carefully conserved for essential use only. The irony is that those who can least afford the extra time and effort are burdened with this extra work. Making basic-rate Internet available to Xoliswa won’t solve her logistical challenges but it is likely to make them easier to manage.

The point here is simple. Free access to basic-rate Internet, or UBI, could have a really big impact on the least connected. We’re not suggesting this replace a national broadband strategy but while we’re waiting for broadband to reach everyone, this could make a real difference right now.

Everyone benefits from UBI. Mobile network operators already know that voice and SMS revenues are shrinking and that the only way they can maintain their revenues is through growth of data services. UBI would help introduce a new generation of data services to those who may not yet see the value of the Internet. And far better to offer a neutral basic Internet than a walled garden. And who knows what the next really useful big platform will be. Perhaps, like 2go, it will come from Africa but if we don’t have a neutral Internet, we are unlikely to find out.

UBI is good for governments, too, because they will be able to legitimately offer online government services to people like Xoliswa without burdening them with data charges.

The “Izolo: mobile diaries of the less connected” study concludes with a set of recommendations. See the report for a detailed explanation of each.

Design for low data consumption

This is an important recommendation but there may not be that much incentive for app designers to do so. Introducing UBI would create a real incentive to design for low data consumption because of the massive additional addressable market available through UBI.

Design for ‘mostly off’

Mobile phones are not really designed to be “off”, although new apps like Google’s Datally app, which literally turns off mobile access except for apps you select, seem to be a step in the right direction. Design for “mostly off” is a great idea, but more as a tool to make the Internet more useful to those who live on the fringes of mobile networks and are often out of range. For those within coverage areas, UBI seems like a better choice. Of course, it is not an either/or situation.

The Web is a world away

It is a hard truth that the Web is not much of destination for most. This may be partly due to affordability issues. If you have an extremely limited budget, you are not going to waste valuable resources exploring the Web for questionable return; you are going to go where you know, which at the moment is Facebook, WhatsApp, etc. Lowering cost as a barrier to access increases the chances of stepping outside the mainstream to discover new things.

Pay attention to the solutions of the less connected

The report does such a great job of highlighting this point. What may look like a connected data subscriber is often someone clinging more tenuously to access than we imagine. Understanding how fragile access is for the least connected should help point directly to the benefits of a UBI strategy.

Public Wi-Fi will not necessarily increase access

Wi-Fi is not a replacement for mobile, but it is a great complementary strategy. If we have learnt anything from access shutdowns and interruptions, it is that we all need redundancy in terms of access. We need both. It is also true that Wi-Fi may become the first connectivity choice in the future for many as Wi-Fi infrastructure spreads and competes with mobile broadband on cost.

Zero-rating services may not lead to broader Internet use

This is such a frustrating point to have to make… “may not lead to”. The only reason we don’t really know the answer to this question is because Facebook, WhatsApp and others engaging in zero-rating programmes refuse to release any public data on them. What, as they say, is up with that?

- Steve Song is founder of Village Telco. This piece was originally published on Song’s blog, Many Possibilities