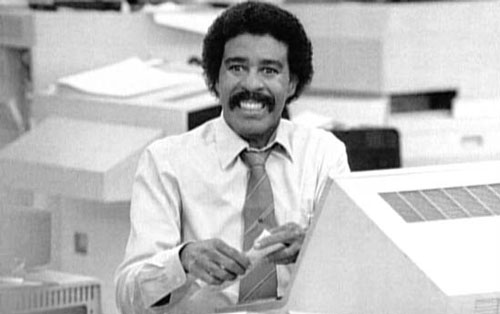

In the film Superman 3, a lowly computer programmer (played by Richard Pryor, pictured) embezzles a fat wad of money from his employer. The boss laments that it will be hard to catch the thief, because “he won’t do a thing to call attention to himself. Unless, of course, he is a complete and utter moron.” Just then the thief screeches into the car park in a brand new red sports car, radio blaring.

In the real world, embezzlers are seldom so obvious. The traditional way to snare them is to hire an accountant to scrutinise accounts for anomalies. But this is like looking for a contact lens in a snowdrift. So firms are turning to linguistic software to narrow the search.

Rip-offs tend to occur in what gumshoes call the “fraud triangle”: where incentive, rationalisation and opportunity meet. To spot staff with the incentive to steal (over and above the obvious fact that money is quite useful), anti-fraud software scans e-mails for evidence of money troubles. Phrases like “under the gun” and “make sales quota” can indicate that an employee is desperate for a bit extra.

Spotting rationalisation is harder. One technique is to identify those who seem unhappy about their jobs, since some may rationalise wrongdoing by telling themselves that their employer is an evil corporation that deserves to be ripped off.

Ernst & Young, a consultancy, offers software that purports to show an employee’s emotional state over time: spikes in trend-lines reading “confused”, “secretive” or “angry” help investigators know whose e-mail to check, and when. Other software can help firms find potential malefactors moronic enough to gripe online, says Jean-François Legault of Deloitte, another consultancy.

To work well, linguistic software must adjust to the way different people talk. For example, when software gurus at Ernst & Young looked at e-mails among financial traders, their first impression was that “these guys’ hair is on fire”, recalls Vincent Walden, a fraudbuster at the firm. The e-mails were packed solid with swear-words. But this is how traders normally talk. It is when they go quiet that the software must prick up its electronic ears.

Dick Oehrle, the chief linguist on the project, explains how it works. First, the algorithm digests a big bundle of e-mails to get used to employees’ language. Then human lawyers code the same e-mails, sorting things as irrelevant, relevant or serious. The human feedback and the computers’ results are then reconciled, so the system gets smarter. Oehrle says the lawyers also learn from the computers (presumably such things as empathy and the difference between right and wrong).

To find employees with the opportunity to steal, the software looks for what snoops call “out of band” events: messages such as “call my mobile” or “come by my office” suggest a desire to talk without being overheard. E-mails between an employee and an outsider that contain the words “beer”, “Facebook” or “evening” can suggest a personal relationship.

Your e-mails may be aired in court

Financial Tracking Technologies, a firm based in Connecticut, goes a step further, making software that can go through calendar apps and travel-expense claims to determine who has come into contact with certain outside investors. This can be married with information about the timing of trades: for example, a short sale before the public release of bad news, says Tony Turner, the company’s boss.

Or consider a broker who e-mails someone a question about the trading volume at which a certain stock would be likely to rise (or fall). This might indicate an interest in manipulating the price. So the software will sift through other data to see if the broker would benefit, even indirectly, perhaps by increasing the value of a derivative in his personal portfolio, says Frédéric Boulier, a Paris-based director of Nice Actimize, an American firm.

Employers without such technology are “operating blind”, says Alton Sizemore, a former fraud detective at America’s FBI. They often pursue costly investigations based on hunches, which are usually wrong, he says. Sizemore, who now works for Forensic/Strategic Solutions, an anti-fraud consultancy in Alabama, reckons that nearly all giant financial firms now run anti-fraud linguistic software, but fewer than half of medium-sized or small financial firms do.

So there is plenty of room for growth. Nice Actimize says its revenues are steadily rising, though it declines to give figures. Prospective users typically pay for a single “snapshot” search of 12 months of company records, according to Apex Analytix, a developer of the software in Greensboro, North Carolina. For a company with 10 000 employees, this costs about US$45 000. Unless a company is very small, evidence of fraud almost always surfaces, convincing clients to sign up for a yearly package that costs three or four times as much as a spot-check, says John Brocar of Apex Analytix.

Why spend the money? Partly because no one likes to be ripped off. But also because laws on bribery (which is harder to spot than theft) have grown tougher. American bosses can in theory be jailed if their underlings grease palms. Jonas Dischl-Luell of AWK Group, a Swiss firm, sells software that scans e-mail addresses to see if any employees are in contact, even indirectly, with officials in corrupt governments. If a company shows it has systems in place to detect this kind of thing, and starts investigating before outsiders do, it may have an easier time in court. — (c) 2012 The Economist![]()

- Subscribe to our free daily newsletter

- Follow us on Twitter or on Google+ or on Facebook

- Visit our sister website, SportsCentral (still in beta)