Vast aspects of contemporary computing will change dramatically in the next half decade, precipitated in part by the enormous demands the ever-growing amount of data mankind is producing place on computing systems.

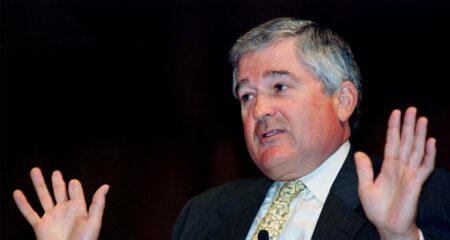

That’s the view of John Kelly, director of IBM Research, who is visiting South Africa this week. He was speaking at Wits University about IBM’s latest list of five predictions for the next five years, some of which the company expects will change the way we work, live and interact.

Kelly says IBM anticipates a move from programmed to cognitive computing in the next few years.

The amount of data is set to double every 12 months for the foreseeable future, meaning various changes to data storage systems will be necessary. Kelly expects that carbon will increasingly replacing silicon in components to improve their performance and the capacity of devices “by orders of magnitude”.

The enormous growth in data volumes isn’t going to come from consumers alone, but from companies looking to model big data and extract uses from it. “If you can model ice flows, you can drill for two extra months a year,” Kelly says, adding that oil companies are willing to invest heavily in such modelling and that “exascale computing” — computers capable of processing more than a quintillion floating point instructions per second – could make it possible.

The bulk of the data generated today, and in years to come, will be images and video, according to Kelly. “This is a mass of unstructured data,” he says. “If you can extract information from [images and video], it could open up whole new worlds.”

Kelly says image analysis is already proving useful in retail and healthcare, particularly in the field of diagnostic imaging.

The history of computing has seen systems move from the early tabulating systems that initiated modern computing to programmable systems of the sort we have today. The next systems era, according to Kelly, is the cognitive.

IBM built a cognitive computer called Watson, which it pitted against human contestants on the US game show Jeopardy. Between the first and second iterations of the computer, IBM was able to get the system to learn from other contestants’ behaviour in addition to learning how questions were structured.

Kelly says Watson is now being used for medical purposes. The goal is to train Watson in diagnostics, including analysing imagery such as scans and x-rays. He argues that the system would, in all likelihood, already pass the Turing test — a measure of cognitive computing that imagines a scenario where a human being could interact with a computer without seeing it and think it’s human.

Ultimately, cognitive computers should be able to predict, interact and learn, says Kelly. In order to expedite this, IBM is also studying the human brain and trying to replicate “neuron and synapse-like computing models” that are based on the manner in which it works.

One of the advantages of this approach is the energy efficiency, flexibility and learning capability such a computing system would afford. “We’ve created a board with the same number of artificial synapses as a worm,” Kelly says. He says the board is capable of playing arcade game Pong, basic image recognition, and even rudimentary learning.

Kelly says one of the dangers of big data is it may become impossible to cope with the volume of information, leading to poor decisions. He says cognitive computing may be able to help ameliorate or reduce this risk. — (c) 2013 NewsCentral Media