Intel’s surprise resolve to stick with chip manufacturing is a move that ought to bring a sigh of relief to leading foundry Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.

Intel’s surprise resolve to stick with chip manufacturing is a move that ought to bring a sigh of relief to leading foundry Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co.

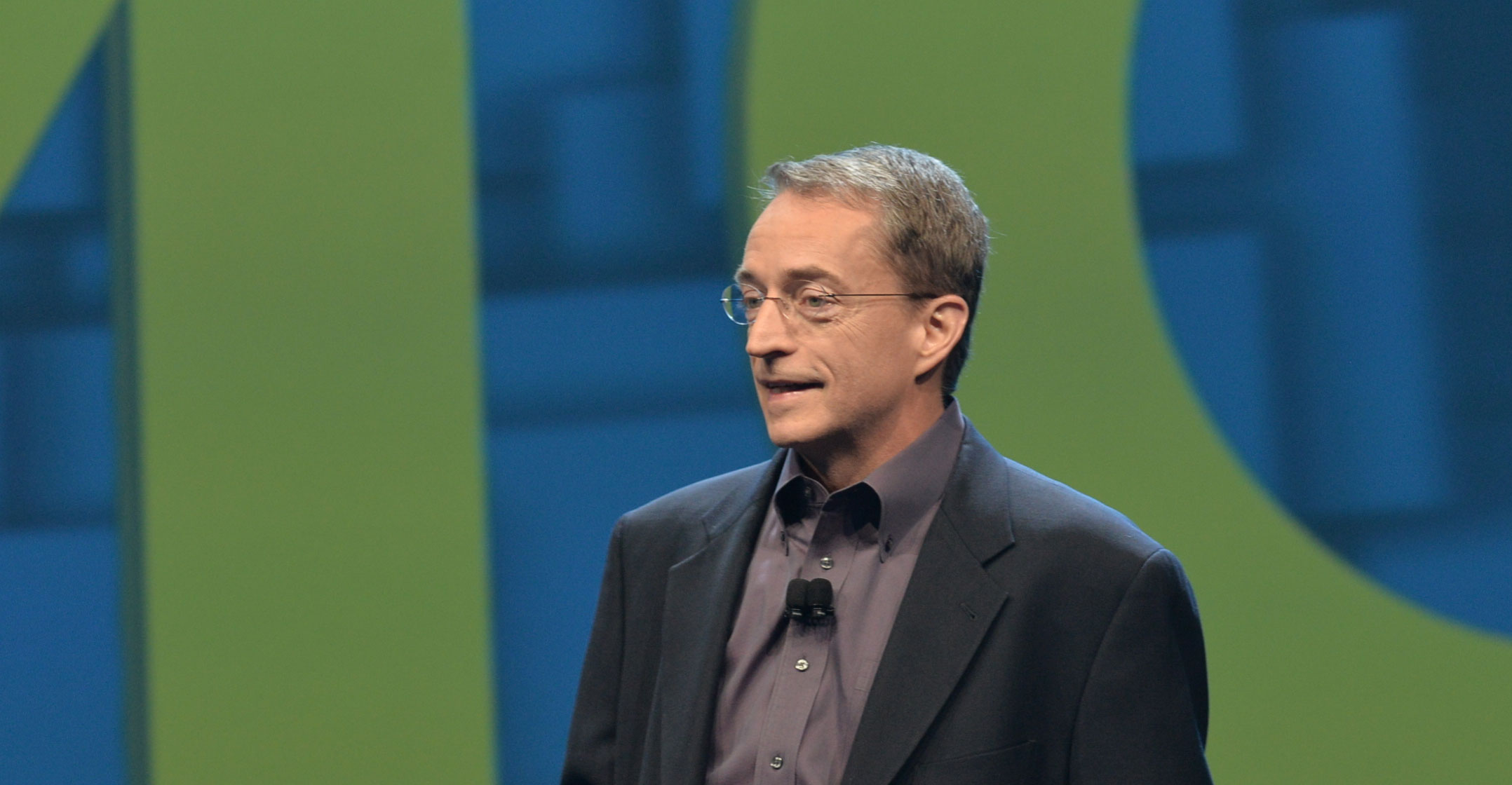

Incoming Intel chief Pat Gelsinger quickly put to rest any notion that it may follow the route taken by contemporaries, including AMD, by ditching production altogether to save the cost of building and running factories. He even doubled down, pledging to chase the high end instead of simply handing this work to custom manufacturers like TSMC.

“We work to close any gaps with external foundries as well as keep ahead,” Gelsinger said overnight in announcing earnings. “And clearly we’re not interested in just closing gaps, we’re interested in resuming that position of the unquestioned leader in process technology.”

That’s a multibillion-dollar sentence right there.

TSMC is planning to spend as much as a record US$28-billion this year to build out capacity for the most advanced semiconductor technology on the planet. Intel, which both designs and makes chips, has fallen behind in production prowess in recent years, while the Taiwanese giant leapt further ahead. So there’s some logic to the notion that the US company just give up altogether.

But with Intel choosing to hang on, the burden won’t fall on TSMC to build capacity for yet another major client.

On the surface, you’d think that adding more Intel to its production manifest would be a boon for the Taiwanese company. And that may be true in the short term, if such orders are stable for years to come.

Multi-year process

Capacity planning and investment is a multi-year process with extremely expensive consequences if you mess up. Most of the cost in manufacturing is the depreciated expense of building factories and installing equipment. But if those machines, some of which cost $150-million apiece, sit idle then the owner is burning money.

To take on Intel’s top-end requirements, TSMC would need to significantly boost its spending in order to create capacity for a sector of the chip industry — computers and servers — that is a large component of the total market yet also an unsteady one.

TSMC already has a high level of exposure to the PC and server sector through two of its largest clients, AMD and Nvidia. Adding more would simply increase, in dollar terms, the gap between the peaks and troughs that occur. Those troughs mean lost money, and Intel’s growth history suggests it may not be the most reliable of clients should TSMC take on a greater share of its production.

It would also increase the regulatory risk. Over the past decade, only Intel and Samsung Electronics could be considered rivals in leading-edge manufacturing. TSMC’s strength has brought attention from regulators in Europe, who may rightfully worry that its dominance poses an antitrust risk. Intel exiting and handing those orders to TSMC would only embolden their case.

Gelsinger, who will take up the post next month, foreshadowed a strategy for his company that much better aligns with TSMC’s best interests: “It’s likely that we will expand our use of external foundries for certain technologies and products.” This would mean more orders to fill up TSMC fabs, but without the massive burden of having to spend billions of dollars to meet leading-edge needs.

Intel investors may be disappointed with the move, but TSMC’s shareholders ought to be delighted. — By Tim Culpan, (c) 2021 Bloomberg LP