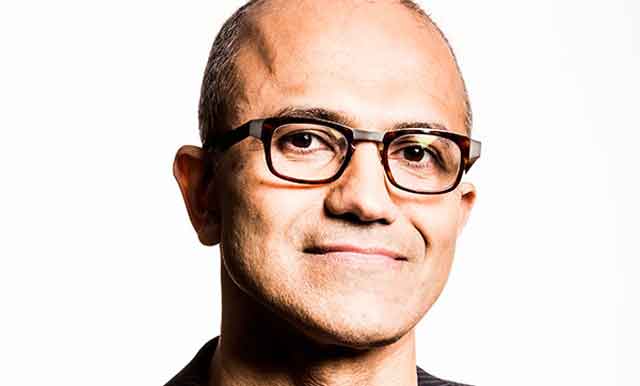

Microsoft is at a crossroads. Its new CEO, Satya Nadella — only the third person to lead the company in its 39-year history, after Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer — has to decide if the software maker’s future lies exclusively in the business market, where it remains strong, or whether it must continue to play in the consumer space, too, where it has lost significant ground to Google and Apple.

Microsoft is at a crossroads. Its new CEO, Satya Nadella — only the third person to lead the company in its 39-year history, after Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer — has to decide if the software maker’s future lies exclusively in the business market, where it remains strong, or whether it must continue to play in the consumer space, too, where it has lost significant ground to Google and Apple.

There’s no denying that Microsoft has done incredibly well in the enterprise space. Its software is still used on most corporate desktops and is employed extensively in corporate data centres. Its server and tools business, which Nadella ran for the past three years, is formidable.

In cloud computing, Microsoft, under Nadella’s direction, has made enormous strides in positioning itself as a market leader, at least in the enterprise, by building advanced cloud platforms like Windows Azure that show the company is still capable of innovation and reinvention.

Indeed, some analysts have suggested that Microsoft’s board, in appointing Nadella, is tacitly admitting that the company’s future lies much more in the enterprise market than in the consumer space.

But abandoning the consumer segment would be a mistake.

First of all, it’s not all doom and gloom for Microsoft on this front. It has real potential to become a major player in the living room of the future, where entertainment — television, music, gaming — is delivered on demand over broadband connections.

And its Skype acquisition may allow it to become a serious contender in the global communications business, leveraging the power of smartphones and the ever-expanding reach of mobile broadband.

However, elsewhere in the consumer space, Microsoft is not doing well. It has stumbled badly in smartphones, for example. Like other industry players, it was caught napping when Apple launched the iPhone in 2007 and again later as Google’s Android rose to prominence (and now dominance). The company took far too long to respond and, although its latest Windows Phone software has been generally well received by the technology press, consumers haven’t fallen in love with it like they have with their iPhones and Android devices. Microsoft is also not releasing updates to the platform anywhere near quickly enough.

Retail consumers are also shunning old-school desktop PCs — on which Microsoft built its early fortune — in favour of smartphones and tablets. In smartphones, Microsoft’s market share is in low single digits; in tablets, it has virtually no presence at all in a market that is still dominated by the iPad.

Microsoft responded to the iPad’s success — and to the Android-powered equivalents — with a new operating system, Windows 8, that features the traditional desktop and also a new touch-driven “live tile” interface, meant for use on tablets. But it’s as if the software has a split personality. The new tile interface, which was the default welcome screen on all platforms, including traditional desktops, felt out of place alongside the desktop mode.

The move confused and alienated some users, forcing Microsoft to backtrack a little with a recent update, version 8.1, in which it reinstated the familiar Start button and allowed users to boot straight to the old desktop mode. Rumours are now swirling that Microsoft could reintroduce the full Start menu in Windows 9 when it is released next year. Fairly or unfairly, the message it’s sending is that it doesn’t have a coherent strategy.

In consumer cloud services, Microsoft is also lagging behind. Google has used its dominance in Web search to gain early leadership in a wide variety of new-fangled online services. It’s now pushing some of these products, like its Web-based productivity suite that competes with Microsoft’s Office cash cow, into the corporate market. It’s a direct threat to the software maker, which has responded, somewhat belatedly, with Web-based Office tools of its own.

Indeed, Microsoft plays in many of the same areas as Google, but arguably hasn’t innovated sufficiently and has been too slow to launch its online services outside the US.

Given that choices made by retail consumers are increasingly driving technology adoption in the enterprise, Microsoft would be wrong to give up on the retail space. Without compelling consumer offerings, it could eventually find its enterprise business critically undermined by its rivals. Nadella surely knows this only too well.

- Duncan McLeod is editor of TechCentral; find him on Twitter

- This column was first published in the Sunday Times