The Film and Publications Board (FPB) plans to extend its regulatory reach to the digital space and, in a draft policy document, proposes that all online content distributed in South Africa must be classified by March 2016.

But it won’t be without ruffling a few feathers along the way. Already there are concerns, because the agency has drafted this online regulation policy without consulting stakeholders and the breadth of its ambit could invite abuse.

The draft policy, which the Mail & Guardian has seen, requires that, as of 31 March 2016, no one will be allowed to distribute digital content in South Africa unless it is classified in terms of the board’s guidelines, or a system accredited by the board, and aligned to its classification guidelines, and the Film and Publications Act and its classifications. The FPB logo must also be prominently displayed.

This regulation would clearly apply to major corporates such as Google and Apple, who face “sanctions” if they don’t comply, but it could also affect bloggers or individuals posting video clips online, who in some cases could face legal action.

The primary mandate of the FPB, formerly a censorship board under the apartheid regime, is to protect children from exposure to disturbing and harmful material, and premature exposure to adult experiences; to provide consumer advice to enable adults and the children in their care to make informed viewing, reading and gaming choices; and to make the use of children in and the exposure of children to pornography punishable.

The draft policy requires that anyone who wants to distribute a film, game or certain publications online will have to apply for an online distribution agreement. A prescribed fee, determined by the minister, will be imposed and, after payment, the distributor can classify content on behalf of the board by using its classification guidelines and those of the FPB Act.

New regulations published in March this year have attempted to widen the categories of businesses that must register with the board. This includes online content distributors, for which a fee of up to R750 000, to be determined by the board, is payable.

“In all classification decisions for digital content, the online distributor must ensure that the board’s classification decision and logo is conspicuously displayed on the landing page of the website, the website catalogue of the online distributor’s landing page of the website, at the point of sale and during the streaming of the digital content,” the document states.

It will apply to anyone who distributes or exhibits online any film or game and certain publications in South Africa, including online distributors of digital film, games and certain publications, both locally and internationally.

In response to questions, Sipho Risiba, the chief operations officer of the board, said it would apply to all online distributors, except for newspapers regulated by the Press Council.

“Although the act exempts broadcasters who broadcast content via satellite, except for the broadcast of X18 material/pornography, broadcasters who also stream content online via the Internet will have to comply with this policy,” he said.

Rating systems

The draft policy says the board has entered “transitional” agreements with several online distributors in South Africa who are using classification rating systems not aligned with the board’s guidelines and the act. The draft policy says classification course material and training will be delivered to online distributors’ classifiers.

According to the draft, sanctions can be used as a last resort to prevent industry classifiers from repeatedly making misleading, incorrect or grossly inadequate classification decisions.

For self-generated content, the draft policy says the board will have the power to order an administrator or any online platform to take down content that it deems potentially harmful and disturbing to children of certain ages. If the content is a video clip on a global platform such as YouTube, the board can refer it to its classification committee for classification.

It will be final and binding and the online distributor will be billed for the classification decision and, if not paid, could result in legal action being taken against the distributor.

The board, which falls under the department of communications, said the draft policy had been sent to all online distributors. Companies such as Google, MTN, Vodacom, Times Media and MultiChoice have received the policy but would not comment as they are studying the document.

Telkom and Altech were unable to confirm whether they had received the document, which gives stakeholders an opportunity to comment by 28 February next year.

A source in a large corporate business said the company was only aware of the draft policy in response to the M&G’s e-mail request for comment about it.

The Internet Service Providers’ Association (Ispa) was not sent a copy, despite the association calling earlier this month for the introduction of new regulations to be delayed until proper consultations about how to create a credible legal and practical framework had taken place.

A spokesman for the communications department said it had just received a copy of the document and was studying it.

“The policy is not released or approved as yet. What we have is a draft policy that was sent to distributors for comments and inputs,” said Risiba. “Workshops with industry and stakeholders are also planned for the months of January and February 2015. Thereafter, the draft will be tabled before [the FPB] council in March 2015 for final approval.”

He said the document would be made public after that.

Challenges

The draft policy aims to tackle the challenges posed to the board’s ability to classify and regulate content online, given that “media convergence” has fundamentally transformed the way content is distributed and consumed.

Dominic Cull, the regulatory adviser to Ispa, said peer-to-peer content distribution had been overlooked in the document, indicating that proper consultations with stakeholders and the different government departments were needed “in order to have a holistic strategy and not one which focuses on technical solutions and found to be fallible”.

He said one had to wonder about the intention of the draft policy.

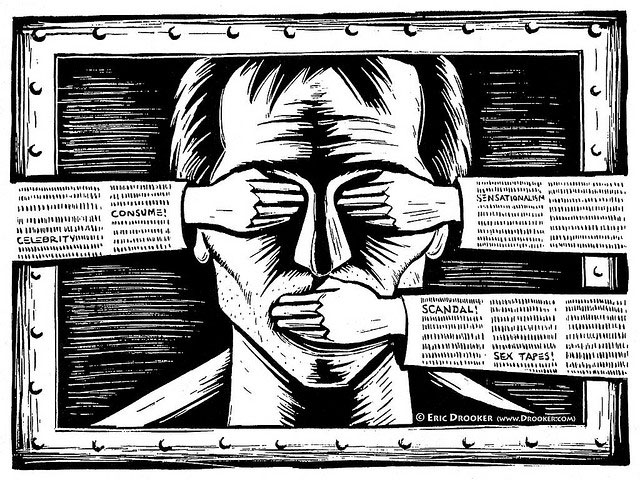

“There is a perception that government is seeking to control the message which is communicated to South Africans, and movements in print and broadcasting media indicate this shift, and we should be concerned, especially with the creating of the new communications department,” he said. “Government may be looking to exercise greater control of the message which could be communicated online.”

In the past, the board has tried to classify websites and artwork, for example, assigning a 16N (the recommended minimum age for viewing because of nudity) classification to The Spear, a controversial painting showing an exposed President Jacob Zuma.

Nicholas Hall, an associate at Michalsons, a specialist law firm, said the document contained some positives, such as the ability to “self-classify”, which sought to remedy the slow and arduous process of classification at present.

“The real problem comes in the implementation of these ideals. It seems to be a massive money-making scheme. Every online distributor has to apply for a licence, and the minister, in conjunction with the board, can fully dictate what those fees are going to be. Then you have to have an in-house classifier trained by the FPB, who no doubt will get to dictate those fees, too,” he said.

The big distributors had vested business interests and were likely to comply, but what was most distressing related to self-generated content.

“Do we want to live in a society where they can decide if my home video needs to be classified or not, and charge me for it if they do. And if you don’t pay the bill, it’s a criminal offence?

“This is the same FPB who tried to classify websites and tried to classify artwork. The current regulation is written so broadly and it’s open to abuse,” Hall said. “What alarms me is this is deemed to be appropriate. It’s broad censorship by the board and we have no recourse.”

Risiba said the FPB council and several stakeholders had argued strongly for the need to move from piecemeal responses that applied the existing classification framework to each new technological development to one that was framed in such a way that it could be adapted to broader convergent media trends.

In response to these challenges, the FPB council in August 2014 approved the board’s online content regulation strategy, and the board had recently finalised the review of its legislation, the Films and Publications Amendment Bill 2014, which had “since been submitted to the minister of communications”, Risiba said.

“The bill, once enacted and applied in conjunction with the approved online content regulation strategy, will bring about a legislative framework which will ensure a greater role in the classification of content by the FPB, using the FPB classification guidelines and the act,” he said.

The core objectives of the strategy are to inform and educate the community about the challenges of digital content, to ensure classification and compliance monitoring of digitally distributed content, to partner with national and international regulators on cross-border regulation, and to provide technology for the online content regulation.

Cull said the technology could refer to the filtering of content.

When put to Risiba, he said: “Filtering is one of the features of the ICT [information communications technology] solutions but what is being envisioned is a solution that will enable the FPB to also classify digital content and do online compliance monitoring, which includes the taking down of unclassified and illegal content.”

Risiba said global best practice had been observed in drafting the policy. — Sapa