For the last few years, Barclays’ annual research reports about the music industry reflected the challenges of a business in transition — or, more specifically, one that had slowed a rapid decline but had not returned to growth.

In 2014, as track sales fell, the bank’s report declared that “Streaming killed the download star”; the 2015 edition was titled “Swimming upstream”. But the bank’s latest research report, published in October and titled “Dancing days are here again”, starts with much better news: “2016 is the year recorded music appears to be turning a corner.”

Many US analysts and executives have been making the same claim, particularly since September, when the Recording Industry Association of America announced that recorded music generated 8,1% more revenue in the first six months of 2016 than it did during the first half of 2015.

That growth was driven by the increasing number of streaming service subscribers: there were 10,8m at the end of 2015 but an average of 18,3m during the first six months of 2016. And the good news isn’t just in the US: the UK market was up 10,9%, France 6%, and some analysts are predicting growth worldwide.

“We’ve reached a place where our largest source of revenue is increasing,” says Stu Bergen, Warner Music Group CEO of international and global commercial services. “That is a good feeling after the long decline of physical.”

However, it’s not time to pop the bubbly just yet.

As streaming grows, sales of downloads and CDs are plunging — by 22,1% and 12,7% respectively in the first nine months of 2016, according to Nielsen Music — and it still remains to be seen just how many casual fans will pony up for subscriptions when music is available for free on YouTube and Spotify’s ad-supported tier.

While streaming has been great for the major labels, its economics are rarely as rewarding for songwriters, publishers and even some labels and artists. And so far, none of the companies in the streaming business is making money.

In other words, if this is a turnaround, then it’s a fragile one. “We’re in recovery,” says Michael Nash, Universal Music Group executive vice-president of digital strategy. “It’s one day at a time.”

The good news

So far, the rebound in the recorded music business has been driven by paid subscription services, which together in the first half of 2016 brought in more than $1bn, more than double the $478,6m for the same period in 2015. (That’s 63 % of the overall US streaming market.)

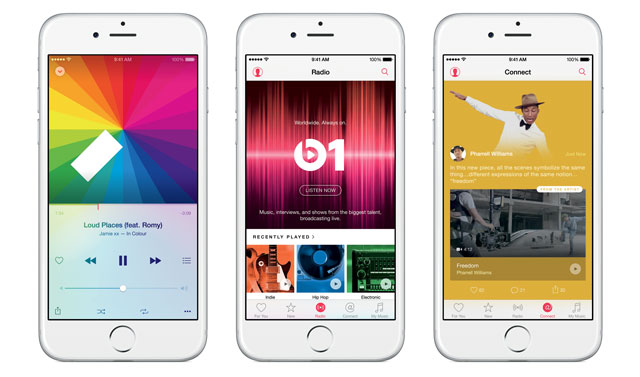

Much of that growth came from Apple Music, which didn’t generate any revenue until the second half of 2015.

“This seems a solid and continuing [trend],” says Martin Mills, founder and chairman of Beggars Group. “I see no reason it would turn back.”

No one knows how big the potential US market for music subscriptions is, but if approximately 100m households have some kind of cable TV subscription and 47m subscribe to Netflix, there’s plenty of room for growth.

“The question isn’t whether we’ll get to 50m streaming subscriptions,” says Russ Crupnick, managing partner of the consultancy MusicWatch. “The question is how long it will take.”

To understand the opportunity this represents, consider that about 42m people in the US bought a downloaded track in the last year, according to MusicWatch, spending an average of between $50 and $60 on music. Broadly speaking, that means each additional subscriber paying $10/month is worth two average downloaders.

One factor that should continue to drive streaming’s success is something the download business never really had: competition. The major labels have a vested interest in Spotify’s success — literally, since together they own an estimated 18% equity in the company — but they also want to be sure one company doesn’t end up controlling the streaming market in the way Apple dominated downloads.

So far, Spotify has a lead in streaming, with more than 40m paid subscribers worldwide, while Apple Music has 17m. Amazon just introduced its own subscription streaming service, which the company is marketing and discounting to its 60m Amazon Prime members. Pandora and iHeartMedia will enter the market in 2017 with the ability to promote their services to the millions of listeners they already have, and Google could make Google Play or YouTube Red serious competitors as well.

“We’re looking at a world with four or five players competing on the core proposition,” says Nash, “and we’re going to see innovation at the high end and the low end.”

The former could involve high-quality audio options from Tidal or Deezer, while the latter could involve lower-priced limited subscriptions, like the $4/month Amazon deal that offers unlimited access to music for one of the company’s Echo speakers.

Promisingly, as the music business starts growing again, investment seems to be following. “I’m getting calls from people in private equity asking me about music assets,” says Doug Davis, a leading entertainment lawyer. “That hasn’t happened for six or eight years.”

The bad news

Even with all the positivity, “we aren’t out of the woods yet”, says Bergen.

However fast streaming grows, it won’t become a stable, sustainable business until it’s profitable for those tech companies. So far, that hasn’t been the case: Deezer postponed its listing in October, Rdio filed for bankruptcy in November, and Spotify’s financial results show that in 2015 it lost $191,4m on revenue of $2,2bn.

A broad economic downturn could hurt Pandora’s stock price or Spotify’s projected listing, forcing those companies to readjust their business models, or even scaring other companies out of the market.

“Eventually these companies have to make a profit for the overall industry to be healthy,” says attorney Joel Katz, who leads the media and entertainment business practice at Greenberg Traurig. “If they don’t become profitable, that could disturb the revitalisation of the record label business, which is coming back in a really good way.”

The streaming business also will require labels to fundamentally change how they operate.

First, they’ll need to shift promotion and marketing efforts to drive consumption rather than transactions.

Second, as smartphones increasingly are used to consume video content, labels need to produce more of it.

Finally, labels have to ensure they don’t help make streaming services so powerful that they will start releasing music themselves, as Apple essentially did with Frank Ocean’s Blonde.

The upshot

Few in the music industry harbour any illusions that things will return to the way they were in 1999, when US revenue peaked at $14,6bn.

Today, music generates money when it’s played rather than when it’s purchased — which adds up more slowly but also more steadily.

“The new market is not like the old market,” says Mills. “New releases generate less immediate revenue than they used to, but their earning span is extended.”

The revenue that labels and other rights holders collect also will be more predictable. The music business always has depended disproportionately on hits, but in a streaming world, the amount of money consumers spend on music won’t vary nearly as much.

“There are very few businesses that survive a 50% revenue decline,” says Nash. “If we do, it’s because we have the big picture in mind.”

- This article originally appeared in the 12 November issue of Billboard