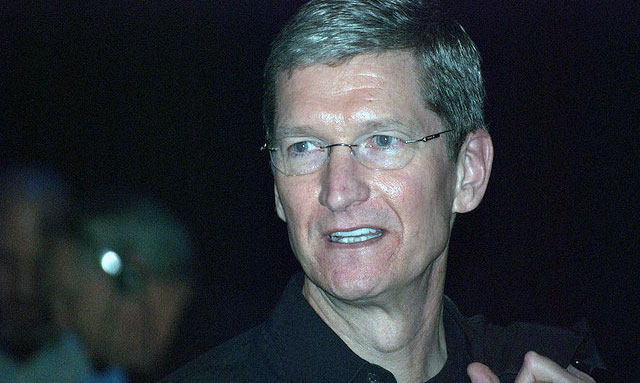

Duan Yongping is convinced Tim Cook didn’t have a clue who he was when they first met a couple years ago. The Apple boss probably does now.

Duan is the reclusive billionaire who founded Oppo and Vivo, the twin smartphone brands that dealt the world’s largest company a stinging defeat in China last year. Once derided as cheap iPhone knockoffs, they leapfrogged the rankings and shoved Apple out of the top three in 2016 — when iPhone shipments fell in China for the first time.

They managed to do it because the American smartphone giant didn’t adapt to local competition, the entrepreneur told Bloomberg in what he said was his first interview in 10 years. Oppo and Vivo employed tactics Apple was reluctant to match, such as cheaper devices with high-end features, for fear of jeopardising its winning formula elsewhere, Duan said.

“Apple couldn’t beat us in China because even they have flaws,” the 56-year-old electronics mogul said. “They’re maybe too stubborn sometimes. They made a lot of great things, like their operating system, but we surpass them in other areas.”

That’s not to say Duan doesn’t appreciate the iPhone maker’s global clout. In fact, the billionaire’s obsession with his US rival is legion: he’s long been a big-time investor in Apple and an unabashed fan of its CEO.

“I’ve met Tim Cook on several occasions. He might not know me but we’ve chatted a little,” Duan said. “I like him a lot.”

When contacted for comment, Apple couldn’t confirm Duan’s meeting with Cook. But Duan has blogged incessantly about Apple’s products, share price and operations since 2013, when the company was worth half what it is today. He needs “a really big pocket” because he carries four devices, including a heavily-used iPhone. In a 2015 post, he argued Apple’s profit should reach US$100bn within five years. Today, Duan won’t say when he actually bought in but says much of his overseas wealth remains tied up in the iPhone maker. He even lives in Palo Alto, an easy drive from Apple’s new UFO-like headquarters in Cupertino.

“Apple is an extraordinary company. It is a model for us to learn from,” Duan said. “We don’t have the concept of surpassing anyone, the focus instead is to improve ourselves.”

Oppo’s gains against Apple may now earn an even broader following for the billionaire dubbed China’s Warren Buffett by local media for his investment acumen. Born in Jiangxi, a birthplace of Mao Zedong’s communist revolution, Duan began his career at a state-run vacuum tube plant before making his name with homegrown electronics.

Duan left the factory floor around 1990, when China was just embracing capitalism and opening industries to private investment. He headed to southern China’s Guangdong province, then the cradle of liberal reforms, to run a struggling electronics plant. His first product was the “Subor” gaming console with dual-cartridge slots — a direct shot at Nintendo’s classic Family Computer, known elsewhere as the Nintendo Entertainment System. The 100- to 400-yuan Subor became a hit in the absence of local competitors. Duan even enlisted Kung Fu star Jackie Chan to endorse the device. By 1995, revenue from the Subor exceeded a billion yuan.

Duan left to set up a new business that year as the operation flourished — a pattern he would repeat in later years. He christened his second venture Bubugao, literally “rising higher step by step”. BBK, as the company came to be known, created a popular line of VCD and MP3 players but later also made DVD players for global brands. Subsidiary Bubugao Communication Equipment Co became one of the country’s biggest feature-phone makers around 2000, going head-to-head with Nokia and Motorola.

It was the first iPhone in 2007 that paved the way for Oppo and Vivo. While they share a common founder in Duan, the sister brands are fierce competitors, trotting out duelling marketing campaigns in markets from India to Southeast Asia. Their salesmanship philosophy plays well in emerging markets, IDC research manager Kiranjeet Kaur said.

“The companies fully understand how to make the best of their people, a specialty they inherited from Duan,” said Nicole Peng, a senior director at Canalys. Importantly, they understood their millennial audience. “Many of their managers are young and have been working at the company since graduation.”

Duan’s latest endeavours were, in part, dreamed up in Apple’s backyard. By 2001 at the age of 40, Duan had decided to move to California to focus on investment and philanthropy, later installing his family in a mansion he reportedly bought from Cisco chairman John Chambers. But the advent of the smartphone forced the entrepreneur out of retirement.

By the second half of 2000s, BBK was on the verge of falling apart as sales of its basic devices slowed. The likes of Huawei and Coolpad were making smartphones priced at around 1 000 yuan. That nearly put the company under, Duan recalled.

“We were in serious discussions about how to close the company peacefully — in a way that the employees can leave unhurt and suppliers don’t lose money,” he said.

Those intense brainstorming sessions spawned the two businesses that would go on to embody Duan’s greatest success. In 2005, the entrepreneur and his protege Tony Chen decided to create a new company. Dubbed Oppo, it sold music players but ramped up to smartphones in 2011. In 2009, BBK itself created Vivo, headed by another of Duan’s disciples, Shen Wei.

“Making mobile phones was not my call,” said Duan. “But I reckoned we could do well in this market.”

At first, neither label garnered much attention. The iPhone was captivating users with its revolutionary apps system and elegant interface, while BlackBerrys lorded over the corporate market. But Oppo and Vivo then developed a marketing-blitz approach that relied on local celebrity endorsement and a vast re-sellers’ store network across China. They crafted an affordable image that appealed to a millennial crowd, then tricked out their devices with high-end specs. On the surface, Oppo and Vivo phones now routinely surpass the iPhone on measures such as charging speeds, memory and battery life.

It paid off. The duo together shipped more than 147m smartphones in China in 2016, dwarfing Huawei’s 76,6m units, Apple’s 44,9m and Xiaomi’s 41,5m, IDC estimates. Oppo and Vivo both doubled their 2015 haul. In the fourth quarter, they were number 1 and number 3 respectively — Huawei was second. Their approach worked particularly well in lower-tier cities, where midrange phones became a mainstream hit, said Tay Xiaohan, an IDC analyst.

Duan’s smartphone progeny are also gaining some momentum beyond their home turf. In the fourth quarter, Oppo and Vivo were fourth and fifth in the world respectively. About a quarter of Oppo’s shipments went to markets like India, where it hopes to dig in before Apple establishes a meaningful presence.

“Smartphones are an unprecedented opportunity. We forecast at least for the next 10 or 20 years, there’s no replacement. But we don’t know,” Duan said.

Cook said on the weekend that Apple doesn’t have a specific goal for market share.

“The competition is more fierce in China — not only in this industry, but in many industries,” Cook told the China Development Forum in Beijing. “I think that’s a credit to a number of local companies that put their energies into making good products.”

Duan has increasingly kept his distance from the Chinese smartphone makers despite remaining a significant shareholder (he won’t say how much). He says he prefers to stay out of the spotlight and enjoy California with his journalist wife and kids. In fact, he attends board meetings but claims to get most of his information on Oppo and Vivo from the Internet, to avoid “disturbing them”.

His rivals have been less considerate. Last October, Xiaomi co-founder Lei Jun lambasted competitors who build dense store channels in rural areas in pursuit of quick sales. In an interview with China Entrepreneur Magazine in October, Lei accused such players of using “imbalanced information” to trick buyers into shunning Xiaomi, precipitating its decline from the top spot.

“Those who said this were insane,” Duan said without naming names. “When someone talks about an information imbalance, deep down they believe consumers are idiots.”

His most visible passion these days is stock investment, which is why he agreed to pay a then-record $620 100 in 2006 to lunch with Buffett. Quotes from the Sage of Omaha still pepper Duan’s blog posts, right alongside tips on golf and Apple.

Duan cemented his reputation as a savvy financier in part by digging his friend, Netease founder William Ding, out of a hole. Ding’s Internet company tanked to as low as $0,13 after the dot-com bubble burst, then almost became the first US-listed Chinese company to get tossed off the Nasdaq over an auditing issue. Duan came to his friend’s aid, buying about 5% of Netease with just $2m in 2002, when the stock price averaged $0,16. Company filings show he still held just over four million shares as of March 2009, but Duan said he sold much of that when Netease hit $40.

His other much-studied holding is premium liquor company Kweichow Moutai Co. He said he bought in at 180 yuan in late 2012. While it nearly halved in 2014, Moutai today trades above 370 yuan.

Duan isn’t shy about talking up his trades, not least of which is Apple, which remains near a record high despite a rare sales decline in 2016. But looking back on his decades as first entrepreneur then stock-picker, his proudest moments remain rooted in BBK. Though he claims to keep it at arm’s length, he admits to worrying about succession and whether the company culture will survive another generation of leaders.

And while BBK’s Vivo and Duan’s own Oppo have done well, there’s no certainty in a fast-moving business. Both are starting to ramp up everything from the features on their phones to marketing campaigns: Oppo notably used Barcelona’s Mobile World Congress to unveil its most advanced camera technology yet, signalling a new maturity.

One thing’s for sure: Duan doesn’t see himself returning to an active executive, leaving others to deal with the next challenge.

“I’ve made it clear many years ago, I will never make a comeback,” he said. “If there’s a problem they can’t fix, then neither can I.” — (c) 2017 Bloomberg LP