A long time ago (1902), on a ship far, far away…

A long time ago (1902), on a ship far, far away…

It is a period of international tensions. Guglielmo Marconi, working from an increasingly cash-rich company, had won his first victory against his competitive nemesis, the Slaby-Arco radio equipment company.

During this pissing match between rival operators, Prince Henry of Prussia got severely annoyed because his urgent ship-to-shore message to his cousin, Kaiser Wilhelm II, was not passed on by Marconi.

Yes, the real Kaiser Chief, who set in motion a drive to establish national control over radio waves.

Spurred on by the various empires’ sinister agendas, new laws were raced through the books, but were incredibly — and stupidly — based on the ownership of the radio devices and where they were located, on property law and national sovereignty, and not more sensibly on precepts of maritime law and other “common heritage”.

Government had seized the radio waves, and now sold them to their richest friends.

At this point, the Star Wars analogy well and truly breaks down, save to ask: “Who will restore freedom to the galaxy?”

It’s a funny story, the history of radio regulation, because right from the start it was a war between private companies trying to cash in, governments trying to assert their power (and cash in), and nationalist politicians asserting the need for iron-clad central control. There is no actual reason for spectrum to be regulated as government-enforced national monopolies, like land. And it must stop.

The anecdote with which I started this column comes from a fascinating paper on the history of radio regulation, and how it’s got us to where we’re going. Early in the development of wireless communication, the radio waves were seized by a combination of nationalist and anticompetitive interests. This fork that regulation took haunts us to this day: instead of being viewed as a “common heritage of mankind”, like space above us, or the oceans, spectrum was “property-ised” on a national basis.

There were some good reasons for this. For one thing, in the early days radio involved very low frequencies. Signals propagated like crazy, filters were not so much brick-wall as undulating putting green, and transmitters’ linearity wasn’t. Interference between transmissions was a very real problem.

The technology advanced quickly, however, but the path that early nationalistic paranoia and commercial lobbying took has been perpetuated through every successive generation of technology.

It has left us with an unbreakably persistent mantra: that spectrum is a “scarce resource”. It is not.

Gold is a scarce resource. You can only find it in particular types of rock, and if you have a licence and pull it out the ground and sell it to someone, it’s gone, never to return.

Spectrum is more like water. It falls from the skies all over the country, and you use what you need of it. If you use too much and the dams are pumped dry, they fill again. If one person takes more than their share, another suffers. But share, according to your needs, and there is plenty to go around.

We regulate spectrum like we regulate mining rights. We should regulate it like water.

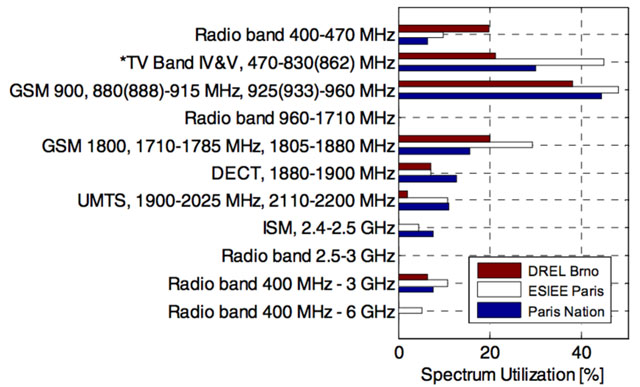

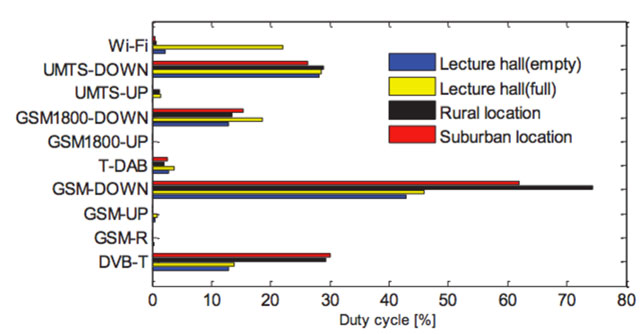

Give “spectrum occupancy” a Google. Page after page of studies, almost universally showing that this “scarce resource” everyone is fighting over is barely used. This is an occupancy study for several European cities in 2010:

This was done in the Czech Republic in 2012 (note: this is “optimistic case”):

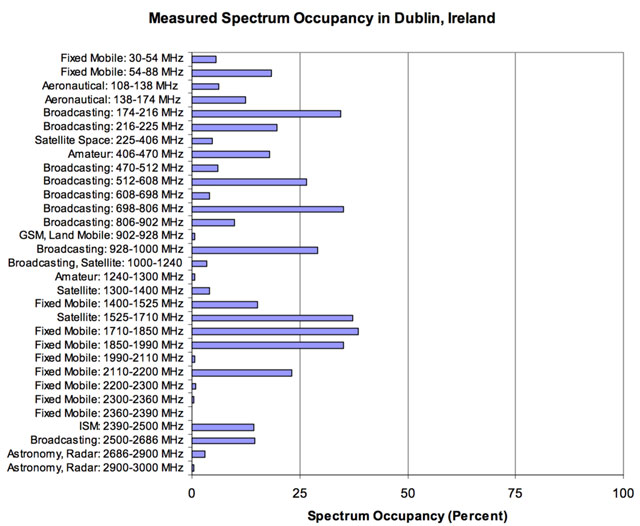

In Dublin, Ireland from 2007:

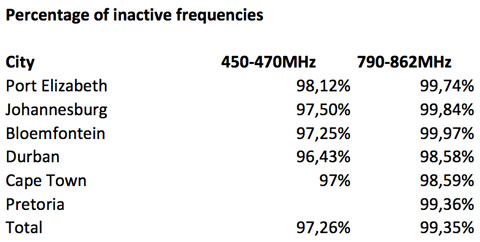

What about South Africa? We’ve been waiting for several years for a full audit of South Africa’s spectrum use, but a couple of ranges were audited by communications regulator Icasa (albeit with inadequate resources). And guess what? In the ranges 450-470MHz and 790-862MHz, occupancy was:

This is “high demand” spectrum.

Today, even in urban areas — with highly efficient and heavily utilised 3G and LTE bands — occupancy is in the 15%-25% range. You get big bursts of traffic, but lots and lots of silence. Useless silence. The network operators that coughed up big money for the licences don’t get any revenue out of it, and neither can anyone else.

That’s because spectrum is seen as a “scarce resource” that needs to be parcelled out bit by bit, and clung to even when it’s clear there’s no benefit to anybody of holding on to it.

It’s seen as a scarce resource for reasons that were either wrong from the start, or have become wrong because technology has moved on.

And how the technology has moved on! Cognitive radios, software-defined radios, Mimo and beam-forming antennae — modern radios can use a huge and wide range of frequencies, and jump from one to another in a split second, with incredibly narrow beams that can follow the receiver.

The ability for a secondary user to opportunistically use spectrum that is not currently being used by its primary user is not a radical idea. It’s there. It’s done.

In South Africa the CSIR has conducted two trials, one in Cape Town and one in Limpopo, to show that television white spaces technology works, and works without causing any interference. It can be done on a time basis, a geographic basis, or noise floor basis (underlay transmission).

TV white spaces is just a small subset of dynamic spectrum access. This week, the global Dynamic Spectrum Alliance Summit is being held in Manila. Today (5 May) in Johannesburg, Icasa is hearing submissions from industry about this new dynamic beast that has the potential to upset the old order.

And it will upset the old order. Large mobile operators and telecommunications link providers spent a fortune of billions of rand on licences. The cosy arrangement between big telecoms operators and government is a Gordian knot of back-scratching and naked power-mongering.

But the big operators are also looking at dynamic spectrum with a schizophrenic eye — they are terrified of the competition it might unleash, the control they may lose… but they have spent fortunes on their licences. What if they could sublet some of it to secondary users? What brilliant revenue flows could be tapped? What if there was a secondary market in spectrum? Spectrum futures to be traded?

Icasa has shown some promising interest in dynamic spectrum allocation. This can only be encouraged. What the telecoms industry and civil society must do is take on the biggest challenge to dynamic spectrum adoption, namely the generations of wrong thinking that have got us to this place, where licence auctions and central control are like crack cocaine to politicians.

Spectrum is not a scarce resource that must be jealously protected and milked for every cent. It’s a wondrous, never-ending stream of connectivity magic that must be used as wisely and completely as possible.

If you don’t use the gold in the ground, it’s still there for the taking. If you don’t use the water falling from the skies, it disappears into the sand.

- Roger Hislop is an engineer in the research and innovation group at Internet Solutions. He writes here in his private capacity