The calls to break up Facebook — or at least to consider it — are growing louder by the day. On the left, US presidential hopeful Elizabeth Warren got on the antitrust bandwagon early with a plan for dismantling the company and other tech giants, while on the right Republican senator Josh Hawley has mused, “Maybe we’d be better off if Facebook disappeared.” They are just two of many.

The calls to break up Facebook — or at least to consider it — are growing louder by the day. On the left, US presidential hopeful Elizabeth Warren got on the antitrust bandwagon early with a plan for dismantling the company and other tech giants, while on the right Republican senator Josh Hawley has mused, “Maybe we’d be better off if Facebook disappeared.” They are just two of many.

But what exactly is this growing chorus of critics trying to solve by threatening to dismember Facebook? The answers show why their solution would be both inappropriate and ineffective.

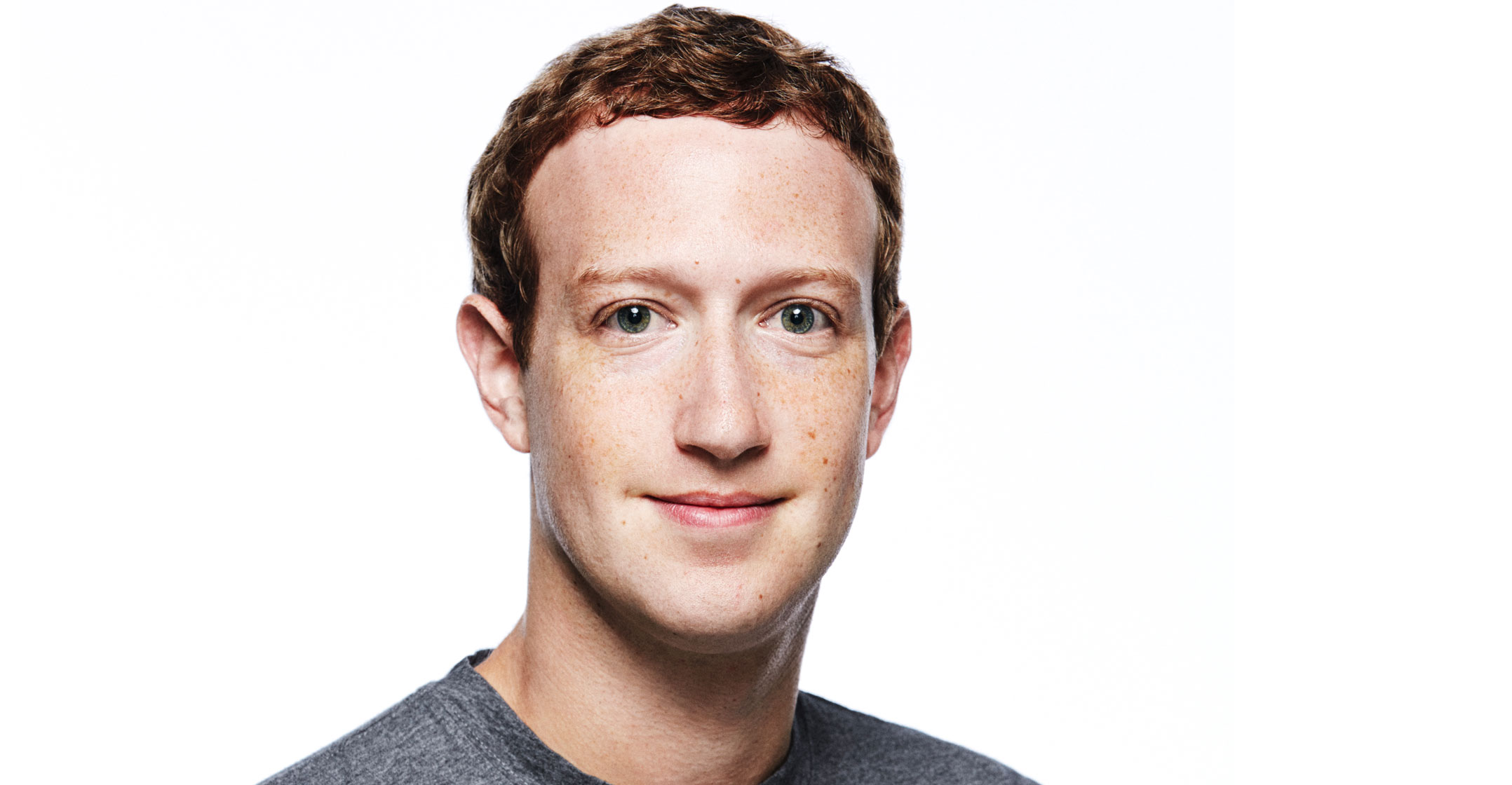

Take the arguments of those who are concerned about privacy. Democratic senator Ron Wyden, for example, went so far as to argue that federal regulators should hold Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg “individually liable for the company’s repeated violations of Americans’ privacy”.

The company records how you are voluntarily using its platform, and sells that information to advertisers. Personal responsibility seems to get completely lost in this discussion. No one is being forced to use Facebook. If you don’t want your personal choices and parts of your life in the public domain, then keep them off social media.

Regardless of your views on the importance of individual responsibility, breaking up Facebook would do nothing to protect privacy. Whether there are 10 Facebooks or one hardly matters if you are worried that information about your behaviour is being sold to third parties.

Another common worry is that foreign governments, especially Russia, are using Facebook to spread false information and interfere in US elections. Chris Hughes, a co-founder of the company who now supports breaking it up, argued that in 2016 “Russian actors” manipulated “the American electorate”.

Real concern

This is a real concern, but as with privacy, it’s not clear why having 10 Facebooks rather than one would adequately address this threat. What Russia can do on one social media platform, it can presumably do on several.

Another criticism of Facebook is that it is addictive, impairing cognitive function and the development of healthy interpersonal skills, especially among children. Hawley describes it as “a digital drug — and the addiction is the point”. Valid or not, these fears are linked to the way a social media platform is used and the amount of time spent on it. They wouldn’t be mollified if people had more platforms to choose from.

The same is likely true when it comes to doubts about Facebook’s ability to filter out violent livestreams, stop the spread of racist and hate speech, and protect data. If anything, economies of scale might make it easier for one social media platform to solve these problems rather than 10.

Then there is the complaint that Facebook has too much control over the public debate. But remember that in the decades before Facebook, Google and a few other companies came on the scene, most people consumed news from one of three nightly network television broadcasts and perhaps one or two local newspapers. Breaking up Facebook would make it harder, not easier, for me to access information I might have missed.

Then there is the complaint that Facebook has too much control over the public debate. But remember that in the decades before Facebook, Google and a few other companies came on the scene, most people consumed news from one of three nightly network television broadcasts and perhaps one or two local newspapers. Breaking up Facebook would make it harder, not easier, for me to access information I might have missed.

A related accusation against the company is that it is suppressing viewpoints — content from conservatives, in particular. President Donald Trump and the senator Ted Cruz, among others, are up in arms about this.

Consumer pressure seems like a good remedy here. Conservatives, who are enthusiastic about entrepreneurship, should consider starting rival companies if they don’t like the way Facebook moderates content.

There have been some high-profile cases of right-wing figures being banned (correctly, in my view) from Facebook. But how serious of a problem is this overall?

The complaints from Trump and some conservatives seem odd in light of his 2016 campaign’s effective use of Facebook. And as Vice News reported this spring: “In the Trump era, Fox News has cemented itself as the most dominant news publisher on Facebook as measured by engagement,” regularly beating out the New York Times and CNN, for example.

What about traditional antitrust issues? Facebook’s critics charge that it has stifled innovation and competition, and decreased consumer welfare. There are reports that the government is ramping up an antitrust inquiry of its practices and those of other tech companies.

Absurd

This borders on the absurd. Monopolies charge consumers high prices, while Facebook is free to users. It is competing for consumers by being a top corporate spender on research and development, and ploughing money into innovation. It is experimenting with ways to respond to its users’ concerns about privacy.

Facebook’s acquisition of Instagram is cited as an example of how it suppresses innovation. But in reality, Facebook took a big bet on Instagram’s improbable success, and won. That was a good business decision, not a threat to consumer welfare.

A study released this spring by Edison Research and Triton Digital finds that Facebook has lost 15 million users in the last two years, with declines heavily concentrated among younger people. (The Guardian summarises the situation nicely: “Parents killed” Facebook for young people.) It hardly seems that Facebook is an entrenched, immovable monopoly.

None of this is to say that the company shouldn’t make changes in the way it operates. Privacy questions could be addressed by requiring it to tell users what items of their data have been sold. This would allow users to make better informed decisions about whether, and how, to continue using Facebook.

Criticism of Facebook’s role in the public square could be addressed by requiring that all of its accounts be held by actual human beings, rather than bots, and by requiring that political ads hosted on the platform be labelled. Indeed, in a conversation at the Aspen Ideas Festival with my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Cass R Sunstein, Zuckerberg argued that current laws on political ads are “very out of date”.

If Facebook were required to publish information on which content and users it kicked off its platform, conservatives might have a better yardstick for judging whether the company is biased.

There is a lot of ground between breaking up a company and regulating it. Facebook’s users, and the company itself, might benefit from more regulation, done right. But breaking up one of the most innovative and successful American companies would be a gross abuse of government power. And for nothing. — By Michael R Strain, (c) 2019 Bloomberg LP