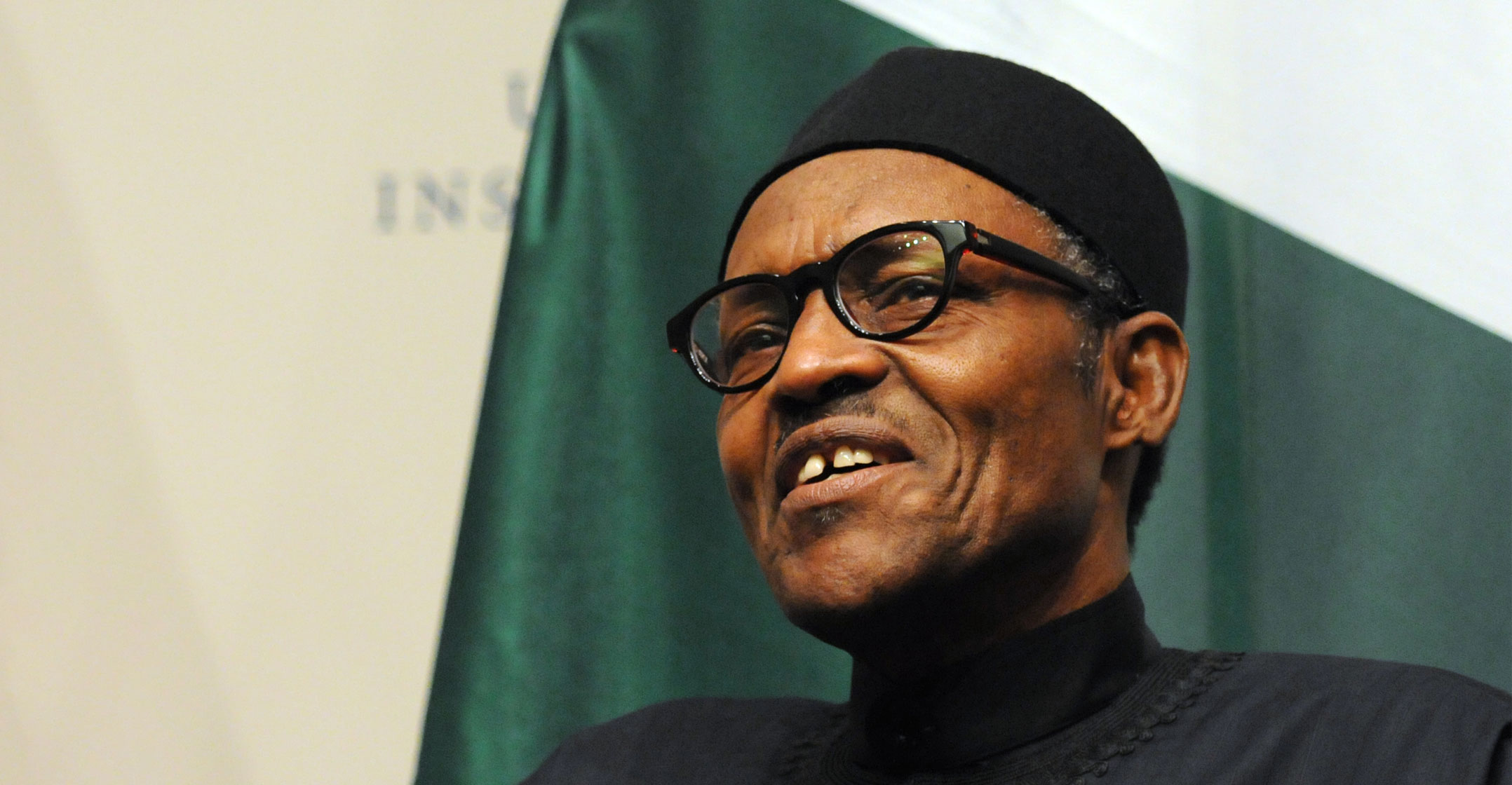

The Nigerian government is waging war on its technology industry. Within the last 12 months, President Muhammadu Buhari’s administration — through different ministries and regulatory bodies — has enacted a series of bans and operational restrictions in the country’s vibrant tech ecosystem.

Most recently, the Central Bank froze the accounts of four fintech platforms this August, claiming they were operating without a licence and trading unethically sourced foreign currencies. The same month, the Nigerian Information and Technology Development Agency proposed introducing tax levies and licensing fees for tech companies as well as prison sentences for those who default on these payments.

Nigeria’s tech hub is one of the most attractive and full of economic potential in Africa. It is home to countless start-ups, two of which, Flutterwave and Paystack, have collectively secured nearly US$400-million worth of investment in just the past year. In a nation struggling with widespread unemployment and poverty, Nigeria’s rapidly expanding tech industry is one of the few beacons of hope for upward mobility, especially among the youth.

Given this, the government’s clampdown on the sector might seem puzzling, especially when several other African countries are actively trying to make their own tech industries more attractive. However, to those familiar with Nigeria’s toxic business and political atmosphere, it is hardly surprising.

Nigeria’s elite has always worked in or with the government, exploiting the system to their benefit. For instance, Africa’s richest person, Aliko Dangote, built much of his empire off government favouritism in the form of exclusive import rights for sugar, cement, and rice, as well as hefty tax credits. This political-business alliance contributes to Nigeria’s culture of impunity. Anything that challenges this elite pact is seen as a danger.

Threat

As economist Tunde Leye puts it: “The main thing we must understand is that the Nigerian elite have a consensus from the North to the East to the West to the Delta, that the formation of wealth independent of the political patronage system is a threat that must be exterminated.”

The threat posed by a young and independently minded “new elite” with access to the global financial ecosystem was never more apparent than during the EndSARS protests in October 2020. These demonstrations began as a movement against police brutality but quickly snowballed into broader calls for government reforms and greater accountability.

The sentiments of the protests were personal to many in the tech industry, some of whom led efforts to build awareness and generate funds for the movement. When traditional financial institutions began freezing accounts linked to EndSARS, for instance, organisers began raising funds through bitcoin instead. By the time the civil society group, the Feminist Coalition, stopped taking donations to support the protests in late October 2020, the cryptocurrency accounted for nearly half of the $387 000 total amount raised.

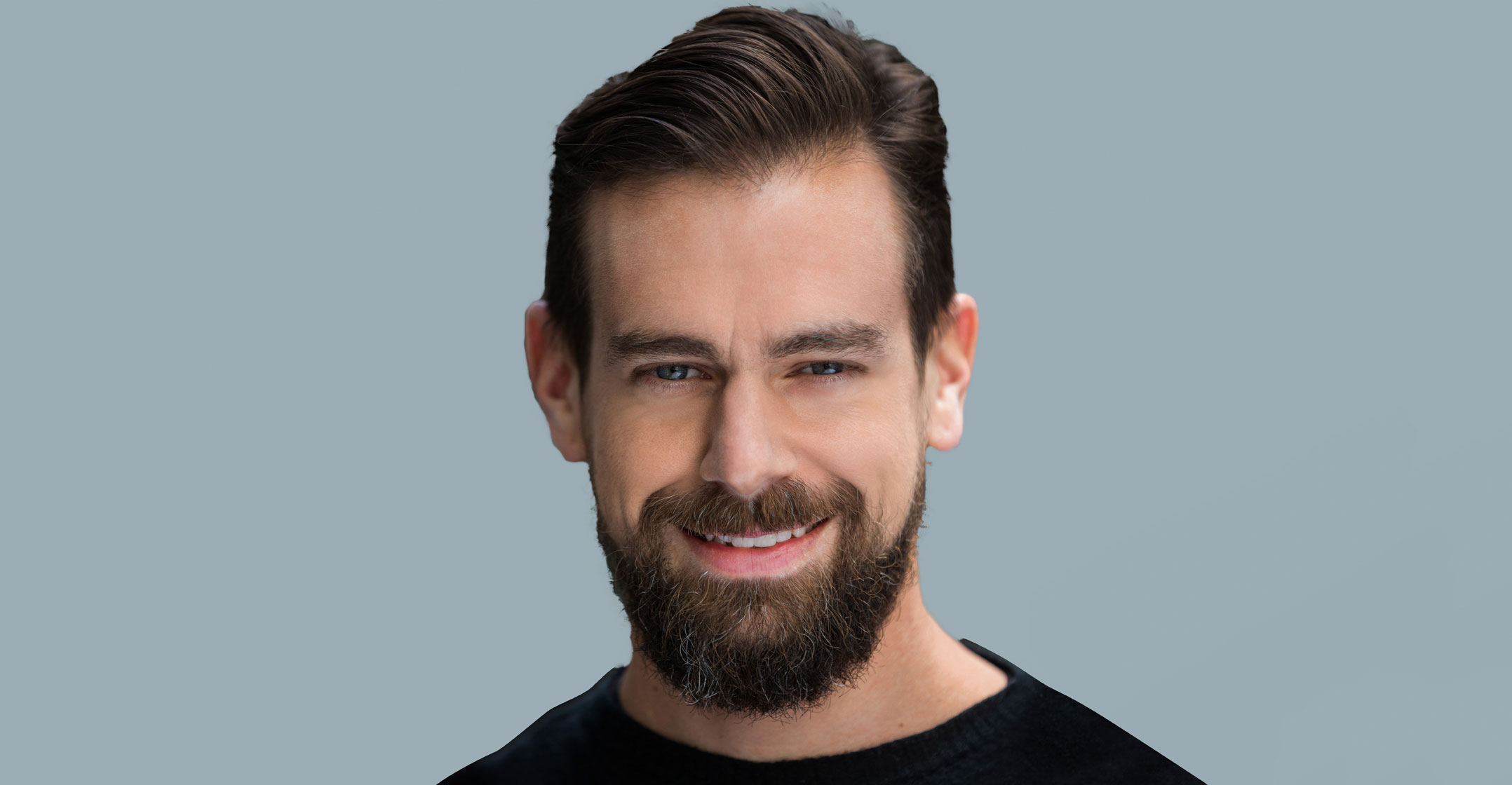

The global traction the movement gained was also in large part thanks to technological platforms such as Twitter, whose founder Jack Dorsey has well-documented ties to Nigeria’s tech industry. Where traditional media failed to provide objective coverage of EndSARS, independent journalists and institutions more than compensated for it on social media.

Having underestimated the ingenuity of the youth and the diverse applications of technology in community organising, the government has since embarked on a punitive expedition against the tech industry. Since the violent crackdown that brought EndSARS to a halt, Nigeria has prohibited cryptocurrency transactions, increased efforts to restrict the use of social media, and outright banned Twitter, a move that has cost the country over $360-million and put thousands of users’ livelihoods in jeopardy.

The government’s unpredictable actions have discouraged many would-be investors, but the political elite would rather torpedo the country’s economic future than relinquish their position as gatekeepers of wealth, power and influence. This will be one of the damning legacies of Buhari’s administration, for whom technology — especially social media — ironically played a decisive part in his ascent to the presidency in 2015.

Nigeria’s young tech professionals are full of anger mixed with incredulity at a government that has given so little and taken so much

Nigeria’s young tech professionals are full of anger mixed with incredulity at a government that has given so little and taken so much. Many responses have fallen into the fight vs flight dichotomy. As policy analyst John Babalola wrote recently, “for a lot of Nigerians, relocating abroad with little or no intent to return has become a life goal”. The country is experiencing a massive brain drain, which has seen many of its best and brightest young minds leave for a chance at a better life.

Yet for other young Nigerians, the open malevolence of the ruling class towards them has only strengthened their resolve to stay and work towards changing things. Political consciousness among the youth is at an all-time high. Realising they cannot innovate their way out of all the excesses of Nigeria’s carnivorous leadership, many young people have resolved to face the problem head on and actively participate in politics. Rinu Oduala, a prominent voice during the EndSARS protests, has emphasised the need to turn attention to seeking reform through the 2023 elections, saying “the momentum of this movement continues to grow as we channel attention towards the education of voters and grassroots mobilisation”.

Nigeria’s young people proved the extent of their power and imagination during the momentous EndSARS protests that reignited almost exactly one year ago. The fate of Nigeria’s political system — and tech industry — may well rest on whether they can leverage their numbers and creativity again in a more formal political setting. — © 2021 AllAfrica Global Media

- Chukwudi B Ukonne is a writer and strategist with a keen interest in Nigerian history, culture and politics. He is a candidate of the inaugural cohort of The School of Politics, Policy and Governance