In last May’s mid-season finale of Mad Men, advertising agency patriarch Bert Cooper dies unexpectedly after watching the live television broadcast of the Apollo 11 moon landing.

The next day, Don Draper has a hallucinatory vision of Bert performing a winsome song and dance routine of what must be the greatest of all deceptive advertising promises: “The Best Things in Life Are Free.”

Cooper’s 1969 death could signify much more: as the second half of season seven begins and the series approaches its conclusion, viewers may witness the stirrings of what — in real life — marked the end of advertising’s modern era.

The burst of creative innovation inspired by the mad men of advertising’s heyday began with the rise of television in the 1940s and concluded in the late 1970s, when giant, publicly traded advertising and media holding companies began gobbling up smaller, creative boutiques, like Mad Men’s Sterling Cooper.

The acquisition binge would result in a loss of creative independence and innovation.

During those halcyon days of the modern era, advertisers, for the first time, crafted messaging with a dual purpose: appealing to consumers’ logic and emotion.

Back then, advertising was primarily a creative endeavor, with messaging honed through market research and focus groups. There was a storytelling element, too: the formulation of big, creative ideas that entertained and engaged consumers through the novel medium of television.

The pioneers of these big, consumer-focused advertising ideas were primarily spearheaded by a few big names: personality-driven males who dominated the business (and still do), along with a few women (like the diminutive but courageous Mary Wells of Wells Rich Green, who may be a model for Peggy Olson’s character).

The pioneers of these big, consumer-focused advertising ideas were primarily spearheaded by a few big names: personality-driven males who dominated the business (and still do), along with a few women (like the diminutive but courageous Mary Wells of Wells Rich Green, who may be a model for Peggy Olson’s character).

The enigmatic Don Draper could be thought of as a cocktail of modern era advertising personalities — one part Bill Bernbach and one part Rosser Reeves, with a twist of George Lois.

Like Bernbach, Draper is known for elegantly integrating art and copy in his advertisements. In a business that previously separated these distinct elements, Bernbach was one of the first “mad men” to wield creative direction over both.

Take Bernbach’s Volkswagen Beetle ad. The small (admittedly unattractive) German import was foreign to American consumers accustomed to bulky, boxy automobiles. Rather than try to downplay the car’s features, Bernbach put them front and centre: “Think Small” and “Lemon” were his spare, Helvetica Bold headlines, which floated in white space above a black and white photo of the Beetle.

The minimalism and directness of Bernbach’s iconic Beetle advertising was original and authentic, resonating with car buyers open to economy, function and style.

Draper also possesses characteristics of the Ted Bates agency’s Rosser Reeves, who was renowned for his development of the Unique Selling Proposition. The gregarious Reeves thought every product must convey its “unique benefit”, the quality that differentiated it from the rest of the competition. If this quality didn’t exist — well, it could be created through advertising.

Reeves believed that once a Unique Selling Proposition was established, the advertising message — the brand benefit — had to be repeated (often within the same ad) to resonate with the consumer. Anacin’s “Fast Relief” ads were an example of his effective and memorable use of the repeated USP brand benefit.

Draper employs Reeves’ USP strategy in an episode when he pitches the “It’s Toasted” tagline to Lucky Strike. The client argues that all cigarette tobacco is toasted. Draper’s reply? “Yes, but you will be the first to advertise it.”

Finally, some of Draper’s excesses could be linked to the antics of temperamentally creative George Lois, who once threatened to jump out a window if a client rejected his advertising ideas. “You make the matzos, and I’ll make the ads!” he once shouted as he stood on the window ledge at a Kosher food company’s Long Island City headquarters. (The client eventually agreed to move forward with Lois’s idea.)

Market warfare and consolidation

Mad Men has given fans a taste of this unique era in advertising. So what happened in the industry over the ensuing decades?

Seismic shifts occurred during the next era of advertising: the postmodern era.

Military-inspired jargon dominated marketing strategies — terms like “positioning”, “offensive warfare”, “defensive warfare” and “flanking” were the battle cries of advertising’s new warriors. The cola, beer and burger wars fought for the hearts, minds — and wallets — of consumers, primarily through television advertising. This lasted until the rise of the Internet (itself a powerful, new advertising medium).

The postmodern era saw the growth and domination of publicly traded, global holding companies. None rose faster — and fell further — than Saatchi & Saatchi, which, at one point, was the world’s largest advertising company.

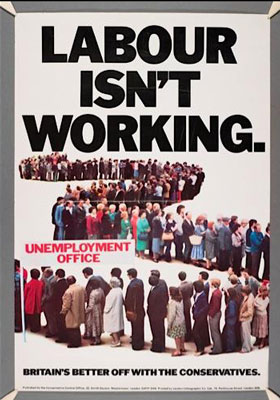

Saatchi & Saatchi, founded in London by two Iraqi immigrants named Maurice and Charles Saatchi, initially gained worldwide attention in the 1970s for its advertising on behalf Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative Party.

“Labour Isn’t Working” read its iconic tagline.

“Labour Isn’t Working” read its iconic tagline.

The Saatchi brothers (known among competitors as “Snatch it and Snatch it”) went on an acquisition binge throughout the 1990s that included some of the world’s biggest and most well known agencies. In 1986, it purchased Ted Bates for a staggering $500m.

While ad agencies were growing in size through acquisition, clients sought to grow their market share through aggressive, comparative (sometimes negative) advertising. Before there was Dave, the soft-sell pitchman and founder of Wendy’s, there was “Where’s the Beef?” — Wendy’s attempt to cut into the sales of Burger King and McDonald’s.

Meanwhile, clients took notice that agency principals were getting mega-rich from their advertising budgets. Ted Bates chairman Robert Jacoby reportedly pocketed $100m from the Bates sale alone. Ultimately, disgruntled shareholders ousted the Saatchi brothers in 1994, and the agency was carved into pieces.

The Saatchis demonstrated that the new model for advertising agencies of the future was first and foremost financial; lost were the creative zeitgeist and “mad men” of the modern era.

But advertising, like nature, abhors a vacuum. During the 1980s a new crop of independent, boutique agencies also emerged with a focus on creativity and the fine art of persuasion: The Martin Agency in Richmond, Virginia; Fallon and Carmichael-Lynch in Minneapolis; and Los Angeles-based Chiat Day, which created Apple’s iconic 1984 ad.

Nonetheless, many of these new wave creative “hot shops” were acquired, like their predecessors, by five major global holding companies: WPP, Omnicom, Publicis, Interpublic and Havas.

It’s telling, then, that after Bert Cooper’s death in Mad Men, the agency’s remaining partners sell a majority stake to rival McCann Erikson — thus ending its creative independence.

My prediction for the end of the show’s run? Don Draper — unable to function in the postmodern world of ads, fads, excessive consumerism and toxic agency politics — abandons advertising once and for all. Perhaps he is tossed out by new agency owners for his contempt of the executive “yes men” who replaced his generation of “mad men”. Or he refuses to dumb down his creative visions for increasingly risk-averse clients. (Or, once again, he is caught in the wrong bed at the wrong time!)

More likely, he walks out unceremoniously — empty handed and alone — continuing the desperate search for the authentic life that has eluded him.

He accepts, finally, that the best things in life actually may be free — and not as advertised.![]()

- Craig Wood is lecturer at Indiana University, Bloomington

- This article was originally published on The Conversation