Twitter and Facebook have both sparked the ire of Donald Trump, but the social networks have taken nearly opposite approaches to politics and the US president.

While Twitter this week slapped unprecedented fact-checks on presidential tweets, Facebook has adopted a more hands-off strategy, saying it wants to be the online equivalent of the public square, shying away from judging which politicians’ statements are true and which are false.

In spite of Facebook’s strategy of accommodation, Trump named both companies in an executive order on Thursday aimed at limiting liability protections for users’ posts.

The two companies have millions of users who can sway public opinion, start social-justice movements and even decide elections, but they diverge sharply on the handling of political speech on their platforms.

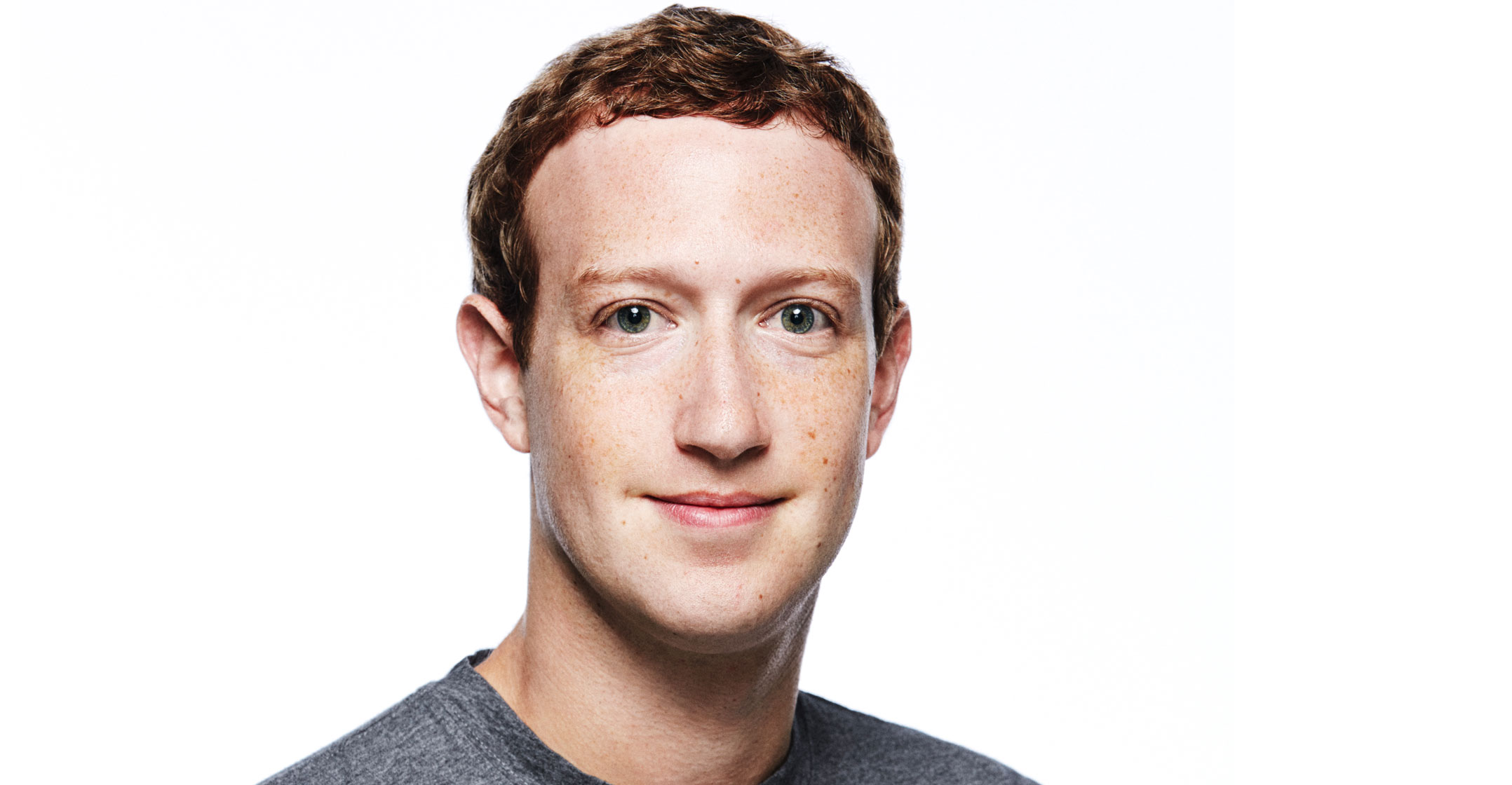

Mark Zuckerberg, co-founder and CEO, is fond of saying that Facebook shouldn’t be “the arbiter of truth”.

Twitter took a giant step in the opposite direction last year when it banned all political advertising. Its decision to slap fact-checking labels on a couple of Trump’s tweets alleging that mail-in ballots encourage voter fraud so infuriated the president — who tweets to his political base to bypass the mainstream news media and whose campaign relies on both Facebook and Twitter — that he’s now seeking to punish not just Twitter, but all social media platforms with limitations on the liability shield.

Risks

The fight touched off a national debate over how to protect online political discourse from dangerous or false information — and raised the question of whether that’s even possible.

The dispute has illustrated the risks social media companies face when they try to act as referees. They are lambasted if they leave demonstrably false content on their platforms unchallenged. Yet they also face a backlash if they take down content or label it misinformation.

That Facebook and Twitter are treating political speech differently is likely no accident, considering the vast differences in their business models and policy risks, experts said. In recent years, Facebook has shifted some of its policies to avoid complaints from conservatives that it’s biased. And as it woos important Republicans who have Trump’s ear, it has angered Democrats with some of its policy decisions.

“There’s a different risk for each company,” said Darrell West, director of the Centre for Technology Innovation at the Brookings Institution. “For Facebook, if they aren’t going to moderate the content, they will become the object of criticism of people who are upset about what appears on the platform,” he said. “The Twitter risk is where to draw the line between freedom of speech and statements that inflame the public or are clearly inaccurate.”

“There’s a different risk for each company,” said Darrell West, director of the Centre for Technology Innovation at the Brookings Institution. “For Facebook, if they aren’t going to moderate the content, they will become the object of criticism of people who are upset about what appears on the platform,” he said. “The Twitter risk is where to draw the line between freedom of speech and statements that inflame the public or are clearly inaccurate.”

Facebook’s perceived drift to the right comes as the US justice department investigates the company and other tech giants over possible antitrust issues, pointed out Harold Feld, vice president of the liberal advocacy group Public Knowledge.

“Facebook now lives in constant fear of an antitrust investigation and relies on the United States to champion its positions abroad in terms of things like taxes on Internet companies and foreign antitrust investigations,” Feld said. “They have a lot of economic incentive to stay in the good graces of the administration and conservative members of congress.”

Twitter, by contrast, is a much smaller company and can act without fear of the antitrust hammer. That gives it more wiggle room to take positions that could upset the party in power, and also a motive to distinguish itself from its bigger rivals. “Nobody is going to accuse Twitter of being a dominant social media platform” or of monopolising online advertising, Feld said.

When asked for comment, Facebook referred to an October speech by Zuckerberg, in which he said: “In a democracy, I believe people should decide what is credible, not tech companies.”

A Twitter spokeswoman directed Bloomberg to a company blog post that says Twitter’s policies are designed to help users “find facts and make informed decisions about what people see on Twitter”.

Under fire

Twitter’s strategy came under fire when the company decided that Trump had made unsubstantiated tweets about mail-in voting on Tuesday. It appended links reading “Get the facts about mail-in ballots”. The labels took readers to a page with a collection of stories and reporters’ tweets about the president’s claims, as well as an item authored by Twitter staff that rebuts Trump, who continued his condemnation of mail-in voting in a tweet on Thursday night.

It was the first time Twitter had taken action against Trump’s posts, prompting him to accuse the company of suppressing free speech. The White House quickly drafted an executive order that would start a review it hopes will lead to a narrowing of the liability protections social media companies enjoy for posts by third parties.

Social media companies “will not be able to keep their liability shield” under the order, Trump told reporters at the White House before signing the order. The liability protection is found in section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act.

The contretemps — and the threat of losing that cherished legal shield — had Zuckerberg taking to Trump’s favourite news outlet to do damage control. “I just believe strongly that Facebook shouldn’t be the arbiter of truth of everything that people say online,” Zuckerberg said in an interview with Fox News. “Private companies probably shouldn’t be, especially these platform companies, shouldn’t be in the position of doing that,” he said, without naming Twitter.

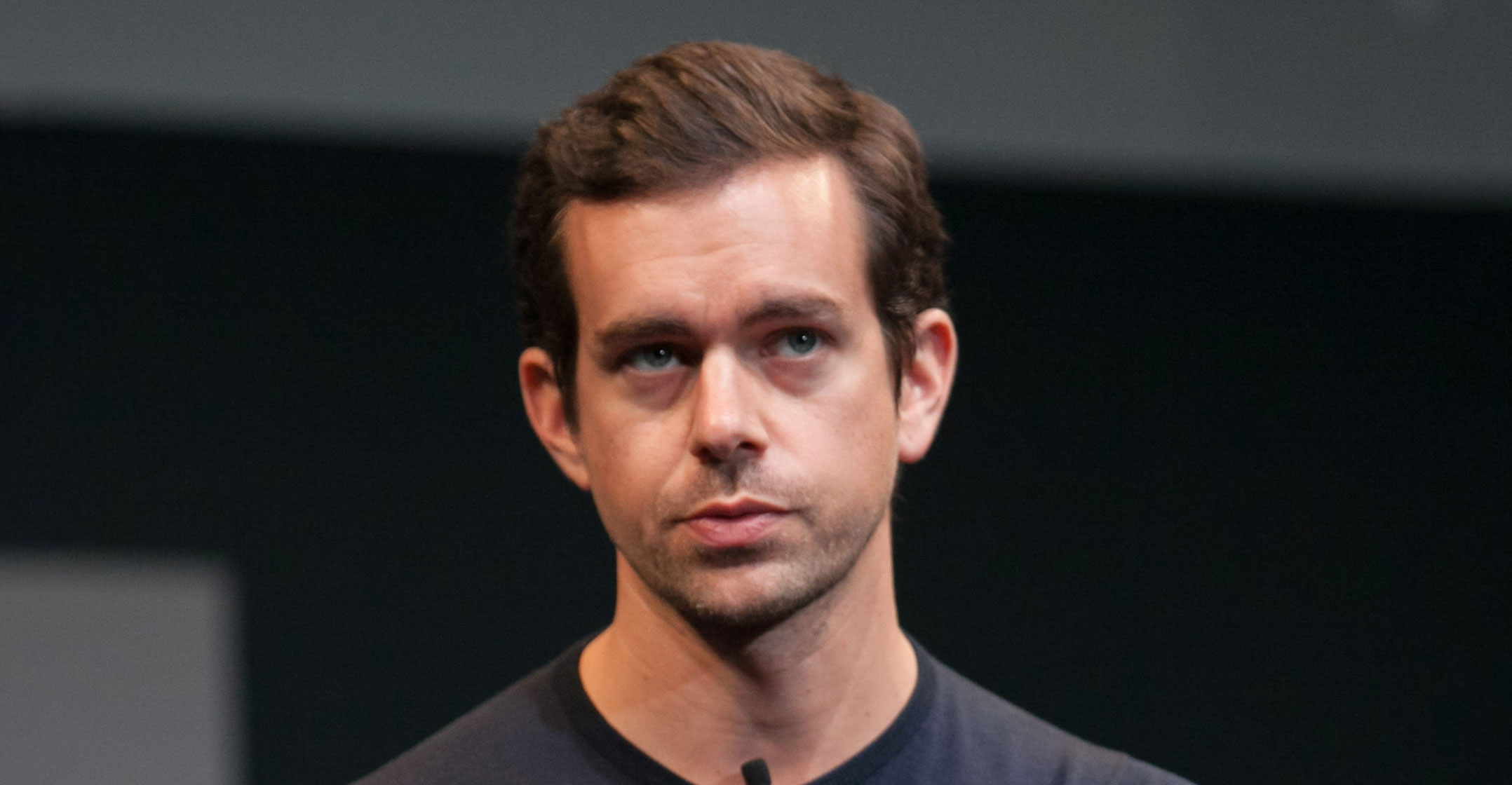

Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey responded in kind. He tweeted that his company would continue to point out incorrect or disputed information. “This does not make us an arbiter of truth,” he said, without mentioning Zuckerberg. “Our intention is to connect the dots of conflicting statements and show the information in dispute so people can judge for themselves.”

Trump used their divergence to put Twitter under more pressure on Thursday evening.

Under Twitter’s policy, posting misinformation is not against the rules, but the company has added fact-checking links to misleading tweets about voting and the coronavirus. Posting misleading tweets about other topics is still fair game.

Most recently, Twitter declined to take action against Trump tweets that encouraged an unfounded conspiracy theory about an aide who died in then-representative Joe Scarborough’s office in 2001 even after her husband publicly asked Dorsey to remove the posts.

Facebook took a different approach. Trump shared the same mail-in ballots post on his Facebook page, but the company said it didn’t violate its standards. Facebook’s policy says it won’t take down false content from politicians except in certain instances, such as posts that spread harmful coronavirus misinformation or encourage voter suppression.

Free speech

Facebook will refer users to articles written by third-party fact-checkers when they encounter false information on other topics on its platform.

Zuckerberg pledged in the October speech that the company would continue to stand up for “free speech” even during controversial circumstances — a position that has won Facebook widespread praise on the right.

“Mark says we don’t think that any of us, referring to tech companies, should be the arbiters of truth. I mean, I think that makes a lot of sense,” said Klon Kitchen, who leads tech policy at the conservative-leaning Heritage Foundation. “I think that any company, especially on political speech, if they try to make themselves into any kind of standard maker, they’re entering into very deep waters fraught with problems.”

Democrats criticised the company last year for failing to take down a manipulated video of house speaker Nancy Pelosi, which showed her slurring her words, suggesting she was impaired during an appearance. Facebook belatedly labelled the video as false, limiting its spread, but the company left up the content.

“They intend to be accomplices with misleading the American people,” Pelosi told reporters earlier this year. “I think their behaviour is shameful.” Twitter also left up the Pelosi video.

Facebook’s free-speech stance took wing after the 2016 presidential campaign, according to people familiar with the matter. In 2016, Alex Stamos, then Facebook’s chief security officer, made a presentation about how the company could curb the spread of fake news to Joel Kaplan, Facebook’s vice president of global policy, Erin Egan, its chief privacy officer, and other executives, one of the people said.

Stamos said the company had the tools to rid the platform of a significant amount of fake news stories based on certain signals, such as when a page was started and how many followers it had, the person said. Kaplan, a former chief of staff to President George W Bush, responded by saying that purging all the fake news would disproportionately hurt conservatives, the person said. The company followed Kaplan’s lead, the person said.

A Facebook spokesman said Kaplan believed that purging all fake news would disproportionately hurt conservatives and that, without a clear rationale, the company should only remove the worst of the worst.

Flagged

While there is little evidence that Facebook, Twitter or Google systematically stifle conservative viewpoints on their platforms, right-leaning groups complain that their posts are more likely to be flagged for violating social media sites’ standards for hate speech or violence when they talk about hot-button social issues such as immigration, religion or sexual orientation.

Since then, Zuckerberg has come to Washington to meet with Trump and other Republican leaders. Facebook also consults right-leaning groups on how they are designing particular policies, such as hate-speech moderation, misinformation, political ads and changes to how news is displayed on its platform, according to multiple conservative groups.

The Facebook spokesman said company executives also meet with liberal-leaning groups. — Reported by Naomi Nix, (c) 2020 Bloomberg LP