By many measures, Turkcell is thriving. It is Turkey’s biggest mobile operator, serving 35m subscribers there and another 30m through subsidiaries and minority stakes in other countries. It boasts 10bn Turkish lira (US$5,6bn) in annual revenues and a market capitalisation of $10,7bn (it is listed in both New York and Istanbul). And all these numbers are likely to grow. In the past year alone, Turkey added more than 3,5m mobile subscribers, yet mobile penetration is only 89%, well short of the EU average of 126% (ie. there are more phones in Europe than people).

But Turkcell is also paralysed by a shareholder dispute. Minority shareholders say they are being trampled — an experience that is all too common in Turkey. The country’s second richest man, Mehmet Emin Karamehmet, is fighting to keep control of the firm he co-founded. His Cukurova Holding, a family-owned group, is pitted against Turkcell’s two other big shareholders, TeliaSonera, a Nordic telecoms operator, and Altimo, a subsidiary of Alfa Group, a large Russian investment firm.

As a result, important decisions are blocked. Turkcell’s shareholders still have not seen a dividend for 2010. Two extraordinary shareholder meetings ended in fiasco last year. The problem is a stalemate on the seven-member board: each big shareholder has two board seats, but five votes are needed to carry decisions. Even though Altimo and TeliaSonera have joined forces, they need the vote of the independent chairman, Colin Williams. TeliaSonera argues that he is not truly independent and is denying shareholders the right of a vote to replace him.

Dynastic trouble

Dynastic trouble

“Turkey is 10 years behind Russia in corporate governance,” says Evgeny Dumalkin of Altimo. That is an exaggeration, but not a wild one. Turkey’s Capital Markets Board, which oversees listed companies, certainly thinks there is a problem. In October, on the eve of an abortive Turkcell shareholders’ meeting, it imposed a new requirement on big companies (now extended to all listed companies) that at least one-third of their board members should be independent.

The deadline for the change is the end of June, when a whole raft of new Turkish auditing rules are due to come into force. True to form, Turkcell’s board has so far failed even to draft new articles of association allowing the addition of two more independent directors.

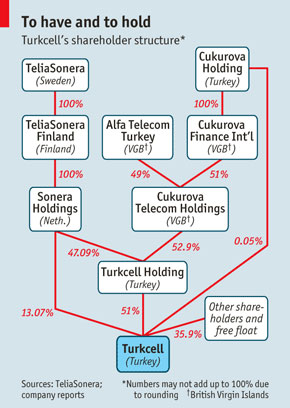

Delay works in Karamehmet’s favour. He has a tenuous 51% control of Turkcell through an inverse pyramid of shareholdings (see chart). If two independent directors were to join the board, that might weaken his ability to block decisions.

Karamehmet’s Cukurova Holding is one of the country’s great industrial dynasties. It grew out of an agricultural business in Turkey’s wild south-east and expanded into textiles and importing John Deere and Caterpillar tractors. By the turn of this century it controlled two banks, and then moved into newspapers, television and digital media. At one time, Forbes magazine reckoned Karamehmet to be the world’s 29th richest man, with $8bn to his name. The publication’s latest estimate ranks him 401st with a mere $2,9bn.

Things started to go wrong in 2002 when the government took over one of Karamehmet’s banks, the ailing Pamukbank, and forced him to sell the other. In 2005, strapped for cash, he agreed to sell part of his stake in Turkcell to Sonera, which is now part of TeliaSonera. He then changed his mind and raised $1,7bn in cash from Alfa, pledging shares in Cukurova Telekom Holding, which controls Turkcell, as collateral.

As a result of these manoeuvres, Karamehmet was hit by double-barrelled litigation. Not only did TeliaSonera claim he had reneged on a sale of shares, but Alfa said he was in default on the loan and made moves to seize the shares that he had pledged as collateral.

As a result of these manoeuvres, Karamehmet was hit by double-barrelled litigation. Not only did TeliaSonera claim he had reneged on a sale of shares, but Alfa said he was in default on the loan and made moves to seize the shares that he had pledged as collateral.

Last September, the International Chamber of Commerce, a body in Geneva that acts as an arbitrator, ordered Cukurova to pay TeliaSonera $932m in damages, plus interest, for reneging on the share deal. In December, in the case brought by Alfa, the British Virgin Islands court of appeal ordered the firm to put $1,4bn in cash, the amount outstanding on the loan, into a special account, pending appeal to Britain’s Privy Council. A hearing to determine whether Cukurova really must put up this cash is set for 8 May.

Karamehmet is no stranger to court action. In 2010, he was given a jail sentence of almost 12 years, suspended pending a retrial, for having used Pamukbank as a cash cow for Cukurova. But despite this track record, forces close to the government would hate to see Karamehmet lose control of Turkcell. The firm’s two competitors, Vodafone and Avea, are already foreign-controlled. Turk Telekom, the incumbent fixed-line giant which controls Avea, was bought in 2005 by Saudi Oger, a group founded by Rafik Hariri, a Lebanese prime minister who was assassinated in 2005.

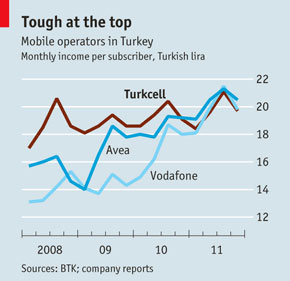

Altimo and TeliaSonera argue that under majority-foreign ownership Turkcell would not become less Turkish. That would be bad for business, since the firm’s first task is to defend its supremacy in Turkey, where Vodafone and Avea already make as much revenue per user.

Turkcell cannot fight back if it is fighting itself. The firm is not wholly paralysed: it recently put in a bid for Vivacom, Bulgaria’s incumbent operator. But acquisitions abroad are no substitute for a harmonious board. Turkcell must clean up its governance, if it is not to become Turksell. — (c) 2012 The Economist