Healthy companies led by competent, commercially successful and globally beloved founders generally don’t tend to fire them. And, as Sam Altman walked on stage in San Francisco on 6 November, all those things could have described his role at OpenAI.

The co-founder and CEO had kicked off a global race for artificial intelligence supremacy, helped OpenAI surpass much larger competitors and was, by this point, regularly compared to Bill Gates and Steve Jobs. Eleven days later he would be fired — replaced by chief technology officer Mira Murati, kicking off a chaotic weekend during which executives loyal to Altman were agitating for his return.

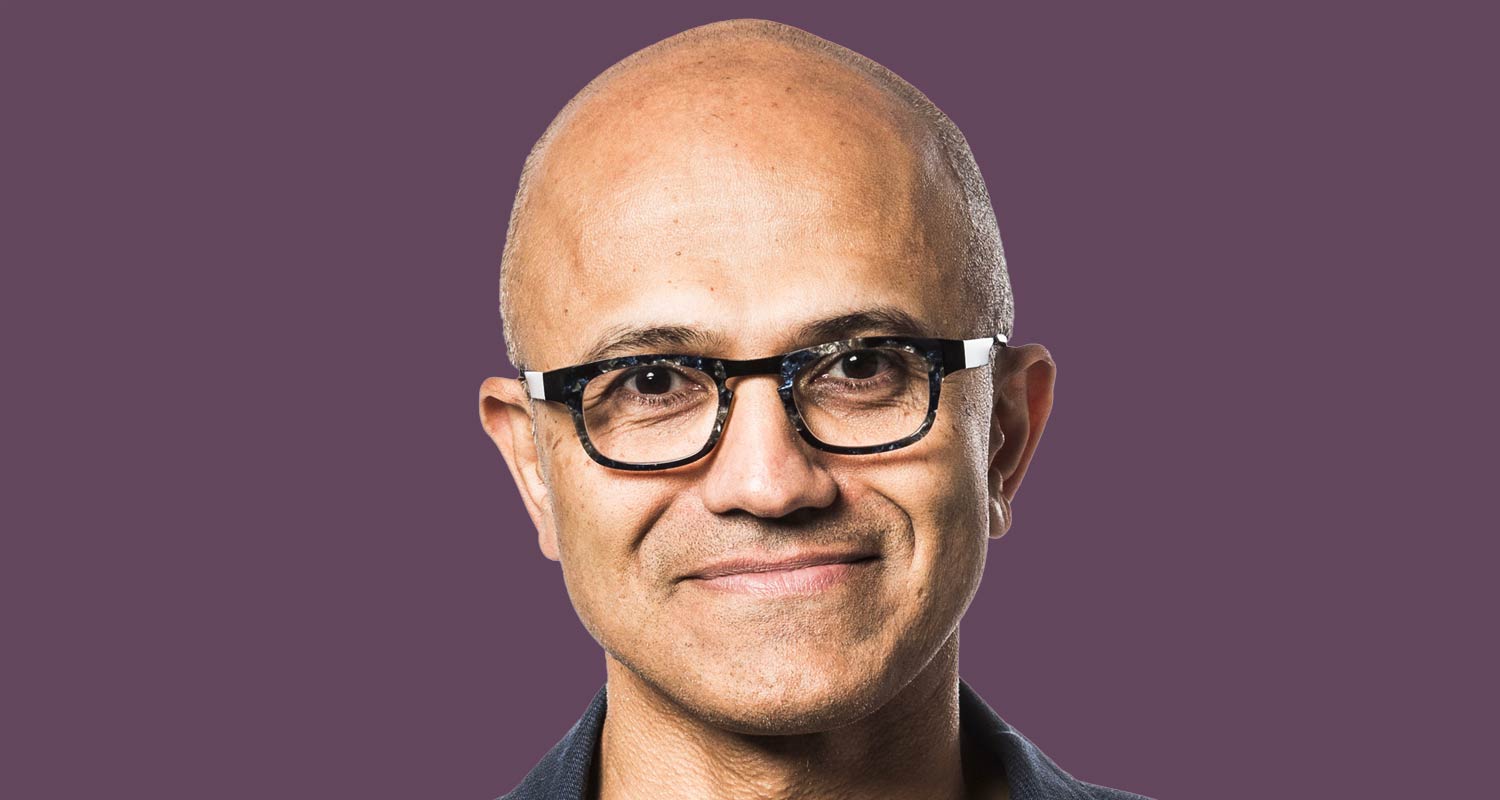

And yet on 6 November, at the company’s first developer conference, the acclaim for Altman seemed universal. Attendees applauded rapturously as he ticked off the company’s accomplishments: two million customers, including “over 92% of Fortune 500 companies”. A big reason for that was Microsoft, which invested US$13-billion into the company and put Altman at the centre of a corporate overhaul that has caused it to leapfrog rivals like Google and Amazon in certain categories of cloud computing, reinvigorated its Bing search engine, and put the company in the leading position in the hottest software category. Now, Altman invited CEO Satya Nadella onto the stage and asked him how Microsoft felt about the partnership. Nadella started to respond, and then broke into laughter, as if the answer to the question was absurdly obvious. “We love you guys,” he finally said after he’d calmed down. He thanked Altman for “building something magical”.

But if customers and investors were happy, there was one constituency that remained deeply sceptical of Altman and the very idea of a commercial AI company: Altman’s own board of directors. Although the board included Altman and a close ally, OpenAI president Greg Brockman, it was ultimately controlled by the interests of scientists who worried that the company’s expansion was out of control, maybe even dangerous.

That put the scientists at odds with Altman and Brockman, who both argued that OpenAI was growing its business out of necessity. Every time a customer asks OpenAI’s ChatGPT chatbot a question it requires huge amounts of expensive computing power — so much that the company was having trouble keeping up with the explosive demand from users. The company has been forced to place limits on the number of times users can query its most powerful AI models in a day. In fact, the situation got so dire in the days after the developer conference, Altman announced that the company was pausing sign-ups for its paid ChatGPT Plus service for an indeterminate amount of time.

Effective altruism movement

From Altman’s point of view, raising more money and finding additional revenue sources were essential. But some members of the board, with ties to the AI-sceptical effective altruism movement, viewed this in tension with the risks posed by advanced AI. Many effective altruists — a pseudo-philosophical movement that seeks to donate money to head off existential risks — have imagined scenarios in which a powerful AI system could be used by a terrorist group to, say, create a bioweapon. Or in the absolute worst case scenario the AI could spontaneously turn bad, take control of weapons systems and attempt to wipe out human civilisation. Not everyone takes this scenario seriously, and other AI leaders, including Altman, have argued that such concerns can be managed and that the potential benefits from making AI broadly available outweigh the risks.

On Friday, though, the sceptics won out, and one of the most famous living founders was suddenly relieved of duty. Adding to the sense of chaos, the board made little effort to ensure a smooth transition. In its statement announcing the decision, the board implied that Altman had been dishonest — “not consistently candid in his communications”, it said in its explosive announcement. The board didn’t specify any dishonesty and OpenAI chief operating officer Brad Lightcap later said in a memo to employees that it was not accusing Altman of malfeasance, chalking his removal up not to a debate over safety, but a “breakdown in communication”. The board had also moved without consulting with Microsoft, leaving Nadella “livid” at the hasty termination of a crucial business partner, according to a person familiar with his thinking. Nadella was “blindsided” by the news, this person said.

Read: Sam Altman will not return to OpenAI: report

According to people familiar with his plans, Altman was plotting a competing company, while investors were agitating for his restoration. Over the weekend, some investors were considering writing down the value of their OpenAI holdings to zero, according to a person familiar with the discussions. The potential move, which would both make it more difficult for the company to raise additional funds and allow OpenAI investors to back Altman’s theoretical competitor, seemed designed to pressure the board to resign and bring Altman back. Meanwhile, on Saturday night, numerous OpenAI executives and dozens of employees started tweeting the heart emoji — a statement of solidarity that appeared equal parts an expression of love for Altman and a rebuke to the board.

A source familiar with Nadella’s thinking said that the Microsoft CEO was advocating for Altman’s potential return and would also be interested in backing Altman’s new venture. The source predicted that if the board doesn’t reconsider, a large contingent of OpenAI engineers would likely resign in the company days. Adding to the sense of uncertainty: OpenAI’s offices are closed all this week. Microsoft and Altman declined to comment. When reached by phone on Saturday, Brockman, who resigned shortly after Altman was fired, said: “Super heads-down right now, sorry.” Then he hung up.

A philosophical disagreement wouldn’t normally doom a company that had been in talks to sell shares to investors at an $86-billion valuation, but OpenAI was nothing like a normal company. Altman structured it as a nonprofit, with a for-profit subsidiary that he ran and that had aggressively courted venture capitalists and corporate partners. The novel — and, as OpenAI critics see it, flawed — structure put Altman, Microsoft and all of the company’s customers at the mercy of a wonky board of directors that was dominated by those who were sceptical of the corporate expansion.

Read: Sam Altman’s axing sends shockwaves through tech

OpenAI’s original goal, when it was founded by a team including Altman and Elon Musk, was to “advance digital intelligence in the way that is most likely to benefit humanity as a whole”, as a 2015 announcement put it. The organisation wouldn’t pursue financial gain for its own sake, but would instead serve as a check on profit-minded efforts, ensuring that AI would be developed as “an extension of individual human wills and, in the spirit of liberty, as broadly and evenly distributed as is possible safely”. Musk, who had been warning about the risks that an out-of-control AI system might pose to humanity, provided much of the nonprofit’s initial funding. Other backers included the investor Peter Thiel and LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman.

The web browser Mozilla, the messaging app Signal and the operating system Linux are all developed by nonprofits

Early on, Musk helped recruit Ilya Sutskever as the company’s chief scientist. The hiring was a coup. Sutskever is a legend in the field dating back to his research on neural networks at the University of Toronto, and continuing at Google, where he worked at the company’s Google Brain lab.

On a podcast earlier this month, Musk said he had decided to fund OpenAI and had personally recruited Sutskever away from Google because he’d become worried that the search giant was developing AI without regard for safety. Musk’s hope was to slow Google down. Musk added that recruiting Sutskever ended his friendship with Google co-founder Larry Page. But Musk himself later became estranged from Altman, leaving OpenAI in 2018 and cutting it off from further funding.

Altman needed money, and venture capital firms and big tech companies were interested in backing ambitious AI efforts. To tap that pool of capital, he created a new subsidiary of the nonprofit, which he described as a “capped profit” company. OpenAI’s for-profit arm would raise money from investors, but promised that if its profits reached a certain level — initially 100 times the investment of early backers — anything above that would be donated back to the nonprofit.

No equity

Despite his position as founder and CEO, Altman has said he holds no equity in the company, framing this as in line with the company’s philanthropic mission. But of course, this would-be philanthropy had also sold 49% of its equity to Microsoft, which was granted no seats on its board. In an interview earlier this year, Altman suggested that the only recourse Microsoft had to control the company would be to unplug the servers that OpenAI rented. “I believe they will honour their contract,” he said at the time.

The ultimate power at the company rested with the board, which included Altman, Sutskever and president Greg Brockman. The other members were Quora CEO Adam D’Angelo, tech entrepreneur Tasha McCauley and Helen Toner, director of strategy at Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology. McCauley and Toner both had ties to effective altruism nonprofits. Toner had previously worked for Open Philanthropy; McCauley serves on the boards of Effective Ventures and 80,000 Hours.

Read: OpenAI CEO Sam Altman launches Worldcoin crypto project

OpenAI isn’t the only ambitious technology project situated inside a nonprofit. The web browser Mozilla, the messaging app Signal and the operating system Linux are all developed by nonprofits, and before selling his company to Musk, Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey lamented that the social network was beholden to investors. But open-source projects are notoriously difficult to govern, and OpenAI was operating at a greater scale and ambition than any tech nonprofit that had come before it. This, along with reports of the company’s extreme financial success, created a backlash that was almost inevitable in retrospect.

In February, Musk complained on X that OpenAI was no longer “a counterweight to Google, but now it has become a closed-source, maximum-profit company effectively controlled by Microsoft”. He reiterated these gripes during a recent appearance on Lex Fridman’s podcast, adding that the company’s pursuit of profit was “not good karma”.

At the same time, Altman was pursuing side projects that had the potential to enrich him and his investors, but which were outside of the control of OpenAI’s safety-conscious board. There was Worldcoin, his eyeball-scanning crypto project, which launched in July and was promoted as a potential universal basic income system to make up for AI-related job losses. Altman also explored starting his own AI chip-maker, pitching sovereign wealth funds in the Middle East on an investment that could reach into the tens of billions of dollars, according to a person familiar with the plan. He also pitched SoftBank Group, led by Japanese billionaire and tech investor Masayoshi Son, on a potential multibillion-dollar investment in a company he planned to start with former Apple design guru Jony Ive to make AI hardware.

These efforts, along with the for-profit’s growing success, put Altman at odds with Sutskever, who was becoming more vocal about safety concerns. In July, Sutskever formed a new team within the company focused on reining in “super intelligent” AI systems of the future. Tensions with Altman intensified in October, when, according to a source familiar with the relationship, Altman moved to reduce Sutskever’s role at the company, which rubbed Sutskever up the wrong way and spilled over into tension with the company’s board.

At the event on 6 November, Altman made a number of announcements that infuriated Sutskever and people sympathetic to his point of view, the source said. Among them: customised versions of ChatGPT, allowing anyone to create chatbots that would perform specialised tasks. OpenAI has said that it would eventually allow these custom GPTs to operate on their own once a user creates them. Similar autonomous agents are offered by competing companies but are a red flag for safety advocates.

In the days that followed, Sutskever brought his concerns to the board. According to an account posted on X by Brockman, Sutskever texted Altman on the evening of 16 November, inviting him to join a video call with the board the following day. Brockman was not invited. The following day at noon, Altman appeared and was told he was being fired. Minutes later, the announcement went out and chaos followed.

The uncertainty, which continued over the weekend, threatened OpenAI’s elevated valuation and Microsoft’s stock price, which dropped sharply as the market closed on Friday. “It’s a disruption that could potentially slow down the rate of innovation and that’s not going to be good for Microsoft,” said Rishi Jaluria, an analyst at RBC Capital Markets. “OpenAI was going at breakneck speed.”

‘Worried’

At the same time, companies that depend on OpenAI’s software were hastily looking at competing technologies, such as Meta Plaforms’ large language model, known as Llama. “As a start-up, we are worried now. Do we continue with them or not?” said Amr Awadallah, the CEO of Vectara, which creates chatbots for corporate data.

He said that the choice to continue with OpenAI or seek out a competitor would depend on reassurances from the company and Microsoft. “We need Microsoft to speak up and say everything is stable, we’ll continue to focus on our customers and partners,” Awadallah said. “We need to hear something like that to restore our confidence.”

If Altman does get his job back, Musk said he’d be “very worried”, he posted on X on Sunday. “Ilya has a good moral compass and does not seek power. He would not take such drastic action unless he felt it was absolutely necessary.” — Max Chafkin and Rachel Metz, with Emily Chang, Ashlee Vance, Shirin Ghaffary, Dina Bass, Jackie Davalos, Edward Ludlow, Julia Love and Ellen Huet, (c) 2023 Bloomberg LP