In all of the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) excitement, we’ve forgotten that it is first and foremost a scientific instrument, created to allow scientists to answer questions that can’t be answered with existing equipment: how are galaxies created? Are there other habitable planets? What is dark matter? What is gravity?

The SKA will be the largest radio telescope in the world, comprising thousands of antennas in Australia, South Africa and other African partner countries. Since it was decided in May last year that the telescope would be split between two continents, scientists and engineers have been working on how this split will work without compromising the science that the SKA is expected to perform.

The rather unwieldy task of designing the telescope has been broken up into work packages, with international consortia submitting proposals.

“All of the consortia are set up, and they were approved by the board at the last meeting [last month],” SKA Organisation director-general Phil Diamond said.

In the next two to three weeks, the consortia would have “negotiation meetings” with the SKA Organisation “setting up the mechanics of interaction between the [SKA] office and the consortia”, Diamond said, mentioning milestones, work reports and the frequency of meetings. “Once consortia know their statement of work, they will be starting work.”

All SKA Organisation members were part of “several work packages, but not all”, Diamond said.

South Africa was involved in a number of these international consortia, said Jasper Horrell, GM for science computing and innovation at SKA South Africa. It would be leading the consortia on assembly and integration, which is “systems engineering to pull everything together to make sure things work on site”; the infrastructure for South Africa, he said.

The country would also play a role in the dish, science data processor and signal and data transport consortia, through industry and academic players.

SKA South Africa had also subsidised companies’ involvement, Horrell said. “We’ve allocated funding on a cost recovery basis … to make it attractive for companies to be a part of this.”

He said that there were agreed milestones, and that companies would be reimbursed “based on delivery”.

While Horrell said that R50m had been allocated over all to these companies for cost recovery, he would not name them until the SKA Organisation had finalised the work packages.

Last month, the SKA Organisation capped the capital expenditure of SKA phase one to €650m. In phase one, Australia and South Africa’s precursor telescopes, Askap and MeerKAT respectively, will be incorporated into what will become the SKA. As part of the bid to host the giant telescope, both countries developed precursor telescopes. The first dish of the 64-dish MeerKAT telescope will be completed by the beginning of next year. The full telescope is expected to come online in 2016.

The SKA Organisation anticipated phase one coming online in 2020, but this is only 10% of the final SKA. This means that phase one — which has a science case of its own that dictates the technical specifications required — has to be able to expand into the full SKA.

According to the draft “SKA Design Reference Mission: SKA Phase 1”, two aspects of the larger SKA science case have been selected as the focus for “SKA Phase 1: understanding neutral hydrogen and pulsars”.

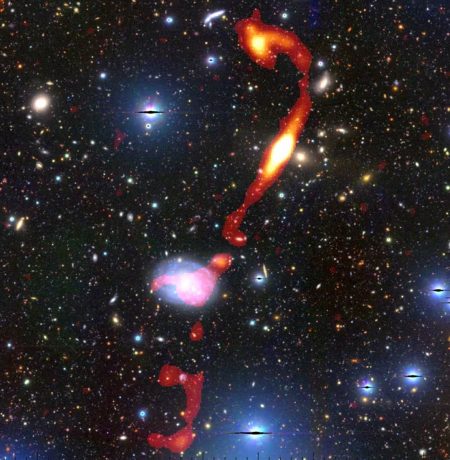

Investigating neutral hydrogen will help scientists understand what happened just after the Big Bang (and also prove that the Big Bang did occur) and how galaxies are formed. Pulsars are massive stars that have gone supernova and emit a strong beam of periodic radio waves. By identifying more of these pulsars — there have in fact been very few useful pulsars identified — scientists would be able to test Einstein’s theory of gravity waves and understand how gravity actually works. — (c) 2013 Mail & Guardian

- Wild is author of Searching African Skies: the SKA and South Africa’s Quest to Hear the Songs of the Stars

- Visit the Mail & Guardian Online, the smart news source