The British government released proposals this week to hold online and social media platforms responsible for harmful content. A few decades ago, we might have scoffed at anyone who even thought they could regulate what people say on the Internet. No longer.

The British government released proposals this week to hold online and social media platforms responsible for harmful content. A few decades ago, we might have scoffed at anyone who even thought they could regulate what people say on the Internet. No longer.

Today, the centralisation of platforms and service providers makes enforcement surprisingly easy. It’s just a matter of picking which layer of the tech stack to hold accountable.

If lawmakers want to prevent the dissemination of certain content on social media, they can cover most of the US population with a phone call to Facebook and Twitter. If governments want more comprehensive coverage, they can hit up the handful of cloud providers that serve up over half the Internet. Problematic websites effectively vanish if deleted from Google, which handles 90% of search activity, and apps can be rendered unfindable if Apple and Google simply remove them from their app stores.

Service providers from infrastructure to social media platforms have, at various times, been pressured to remove users and content for offending our sensibilities. Enforcement is not even limited to the Internet: Airbnb, Uber and Lyft have taken it upon themselves to make travel plans more difficult for those who support racist things.

As it stands, content moderation is mostly reactive, with tech companies taking action only in the wake of public controversy. If an online mob is unsuccessful at pressuring one service provider, it will harass another intermediary. There hasn’t been a consistent target for content removal because a service provider may be uncooperative, or located outside of a censor’s jurisdiction. In the aftermath of the Charlottesville protest and counterprotest, the neo-Nazi website Daily Stormer relocated to a Russian domain, but was ultimately kicked off the Internet by Cloudflare, a content delivery network.

‘Hate speech’

Those who want to ban harmful content generally aren’t after the content itself. The artificial crime of “hate speech” had to be invented because more direct and traditional methods of enforcing certain goals yielded little result. The thing that we really want to get rid of is the fact that some people believe nutty things, sometimes people really don’t like each other, and some people have political views that are simply unacceptable to others.

Censorship tends not to create a world of tolerance. In fact, the idea of restricting “hate speech” was originally championed by the Soviet Union in an effort to silence those who might agitate in favour of capitalism and liberal democracy.

There is one place where regulation would help. Tech companies have nebulous content guidelines with seemingly arbitrary application. Alex Jones, for example, was peddling conspiracy theories on YouTube for over 20 years before the major platforms collectively booted him off. Proactive and specific terms of service would have prevented Jones from ever setting up a YouTube channel.

Social media companies amassed billions of users by promising a platform for free expression. But in their effort to offend nobody, they’ve managed to anger everybody. Now that the population is dependent on a few key services, the platforms need to make difficult decisions but don’t want to take the blame.

Social media companies amassed billions of users by promising a platform for free expression. But in their effort to offend nobody, they’ve managed to anger everybody. Now that the population is dependent on a few key services, the platforms need to make difficult decisions but don’t want to take the blame.

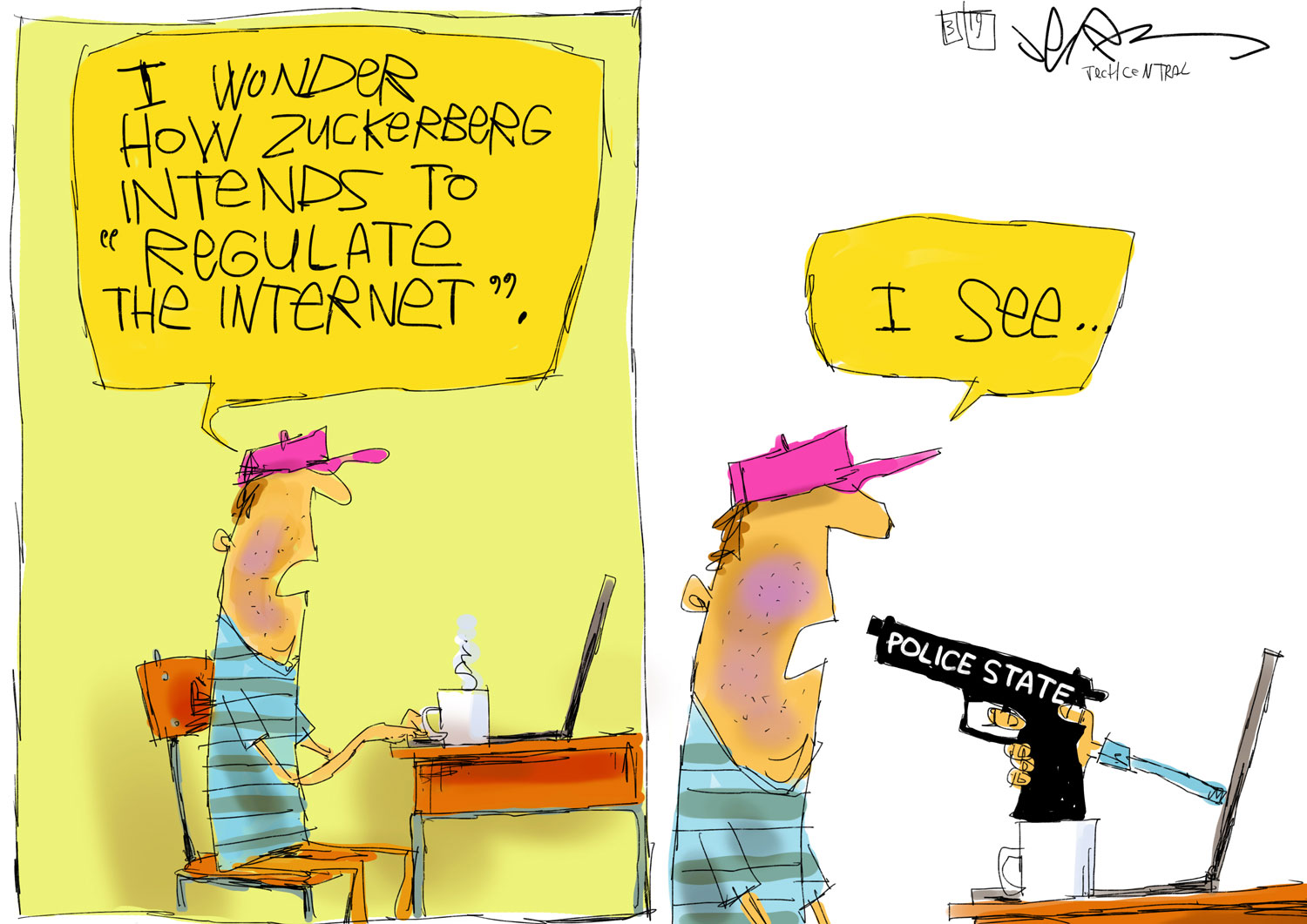

Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg’s proposal for third parties to set global standards governing harmful content will only further entrench existing conglomerates: if you don’t like Facebook’s content policies, you now have no alternative because everyone has to abide by the same rules!

Being proactive about creating specific content rules would have limited the number of users who sign up for any given service. But it also would have encouraged competitors to create alternatives, and prevented truly harmful ideas from being amplified to the general public. In some ways, this creates individual filter bubbles, but I prefer the term safe space.

The purpose of a decentralised Internet, and decentralisation in general, is to constrain the power of a single entity to regulate. As Internet pioneer John Gilmore once put it: “The Internet interprets censorship as damage and routes around it.” Lawmakers can work with major tech platforms to define a narrow range of acceptable content, but they should also allow alternatives to grow. — Elaine Ou, (c) 2019 Bloomberg LP