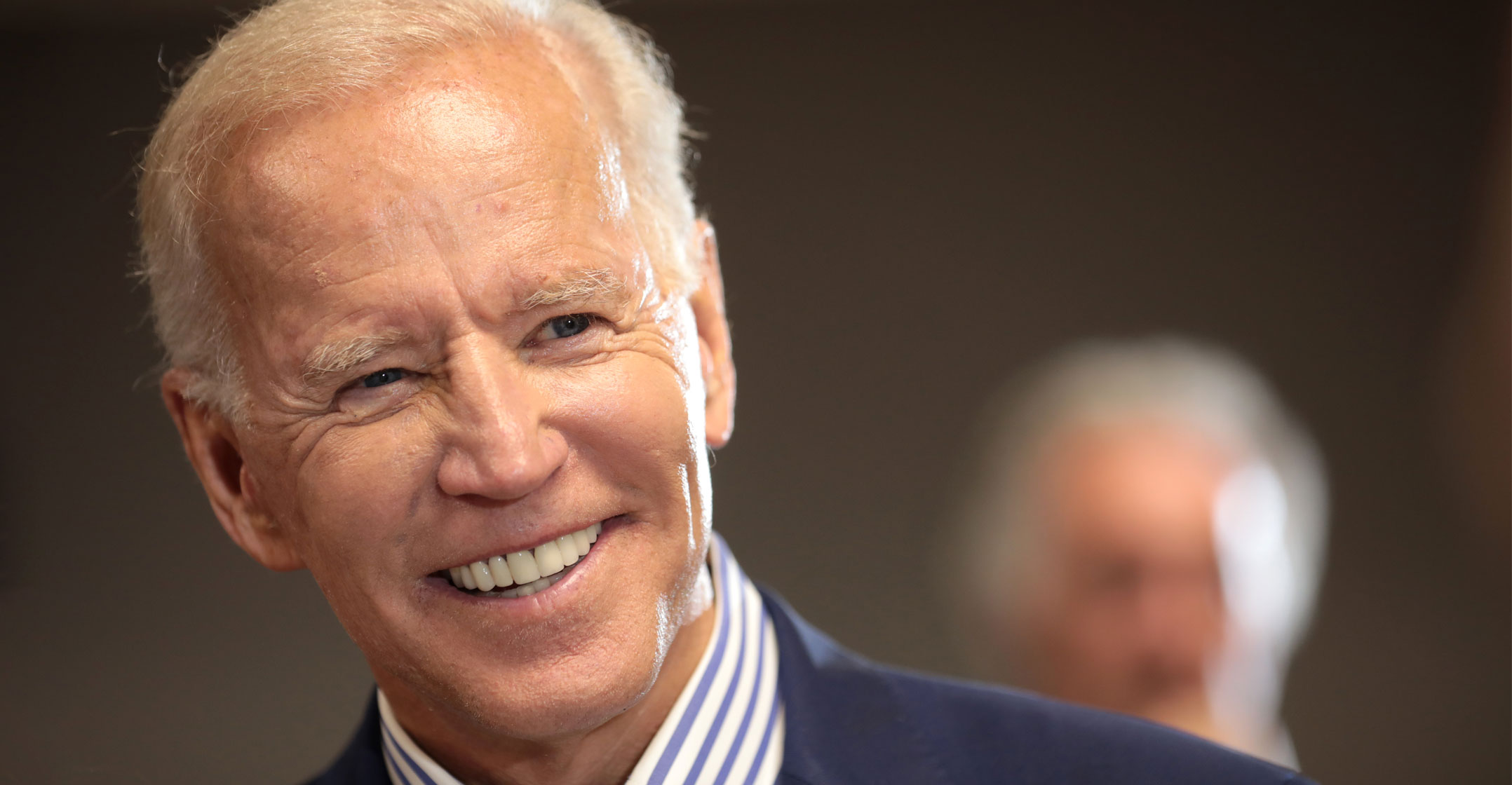

The Biden administration spurned a plan by Intel to increase production in China over security concerns, dealing a setback to an idea pitched as a fix for US chip shortages, according to people familiar with the deliberations.

Intel, the world’s largest chip maker, has proposed using a factory in Chengdu, China to manufacture silicon wafers, said the people, who asked not to be identified because the discussions were private. That production could have been online by the end of 2022, helping ease a global supply crunch. But at the same time, it’s been seeking federal assistance to ramp up research and production in the US.

When presented with the plan in recent weeks, Biden administration officials strongly discouraged the move, the people said.

The situation underscores the challenges of the chip shortage, which has hobbled the tech and car industries, cost companies billions in lost revenue and forced plants to furlough workers. The administration is scrambling to address constraints, but it’s also trying to bring production of vital components back to the US — a goal Intel’s China plan didn’t serve.

In a statement, Intel said it remains open to “other solutions that will also help us meet high demand for the semiconductors essential to innovation and the economy”.

“Intel and the Biden administration share a goal to address the ongoing industrywide shortage of microchips, and we have explored a number of approaches with the US government,” the company said. “Our focus is on the significant ongoing expansion of our existing semiconductor manufacturing operations and our plans to invest tens of billions of dollars in new wafer fabrication plants in the US and Europe.”

Debating

The episode comes as the White House is debating whether to restrict certain strategic investments into China. National security adviser Jake Sullivan has said the administration is considering an outbound investment screening mechanism and is working with allies on what it could look like. President Joe Biden also is set to meet virtually with Chinese President Xi Jinping on Monday.

A representative for the White House declined to comment on specific transactions or investments, but said the administration is “very focused on preventing China from using US technologies, know-how and investment to develop state-of-the-art capabilities”, which could contribute to human rights abuses or activities that threaten US national security.

Like other chip companies, Intel is eagerly waiting for the US congress to pass US$52-billion in funding for domestic research and manufacturing. That proposal, called the Chips Act, has been lingering in the house for months. The president and commerce secretary Gina Raimondo have been pitching the measure as a way to compete with China — as well as preventing supply crunches in the longer term.

Following deliberations with the Biden team, Intel has no plans to add the production in China at the moment, a person familiar with the decision said. Still, such scenarios could arise again, and the administration may need to decide what rules come attached to the grant money.

Some Republican lawmakers have said that the money shouldn’t come without strings attached. They’ve pushed for guardrails to prevent companies from taking the grants and then still increasing their presence in China.

The purpose of the Chips bill is to “ensure less dependence on vulnerable supply chains, including with respect to semiconductors”, according to the White House statement. When asked about potential guardrails in the implementation of the bill, the representative said congress hasn’t yet appropriated the funding.

At the same time, shortages have become a bigger political issue. Car makers are losing more than $200-billion in revenue because of the lack of chips, and workers at idle plants have lobbied politicians to do something about it. Even giant companies with fine-tuned supply chains aren’t immune. Apple expects to miss out on more than $6-billion of sales this quarter because it can’t get enough components.

The $400-billion business has become a key battleground in the increasing rivalry between China and the US

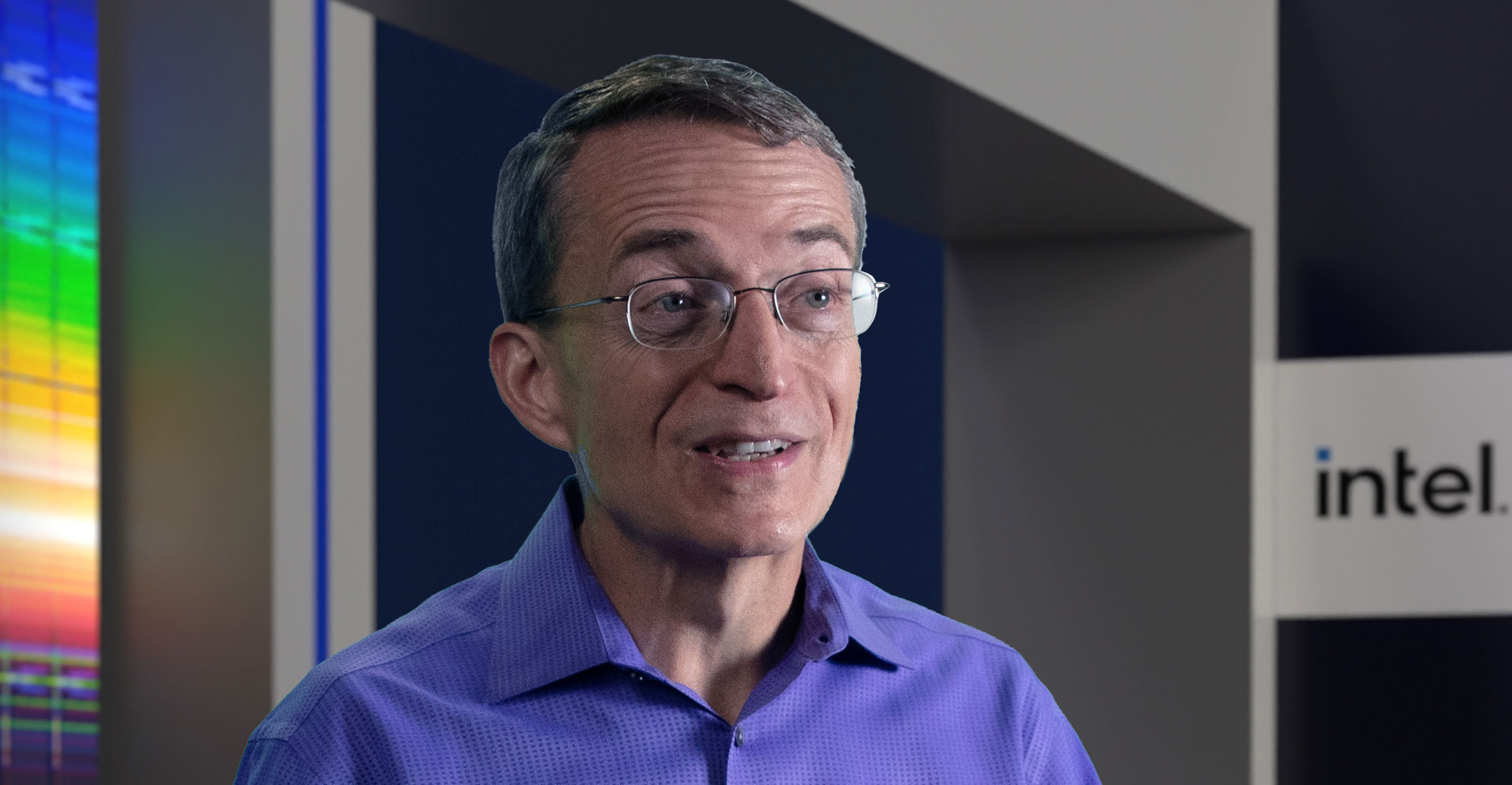

Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger, meanwhile, is trying to cope with the heightened level of public and governmental scrutiny surrounding the chip industry. The $400-billion business has become a key battleground in the increasing rivalry between China and the US, forcing companies operating in the Asian nation to navigate more obstacles.

The chip industry has a complicated relationship with China, one that became much more difficult during the Trump administration’s trade war. China is the biggest consumer of semiconductors for local use, and it serves as the assembly centre for much of the world’s electronics. To help with logistics and to keep Beijing happy, chip makers — including Intel — have located plants there. But they face longstanding US government restrictions that prevent them from exporting cutting-edge semiconductors to the country.

Intel also is trying to take on the world’s biggest contract manufacturers of semiconductors, increasing its production needs — and its potential reliance on China. To challenge the leaders in that industry, TSMC and Samsung Electronics, Intel needs to be able to support Chinese customers or lose out on a huge chunk of the market.

Mounting competition

Intel’s plants have previously only manufactured chips of its own designs, mainly the processors used by the PC industry. But it faces mounting competition from products made by TSMC and Samsung, so Gelsinger’s strategy is to challenge them at their own game. Intel is already opening two new plants near an existing site in Arizona to help with these efforts. The company has also said it will be building in Europe.

Gelsinger has argued that relying too much on outsourced production in Asia is a supply-chain risk. He’s lobbied for public money around the world to support spreading chip-making capabilities to different areas. But TSMC and Samsung aren’t standing still themselves: They’re expanding in new areas, too, including by adding new plants in the US. — Reported by Jenny Leonard and Ian King, (c) 2021 Bloomberg LP