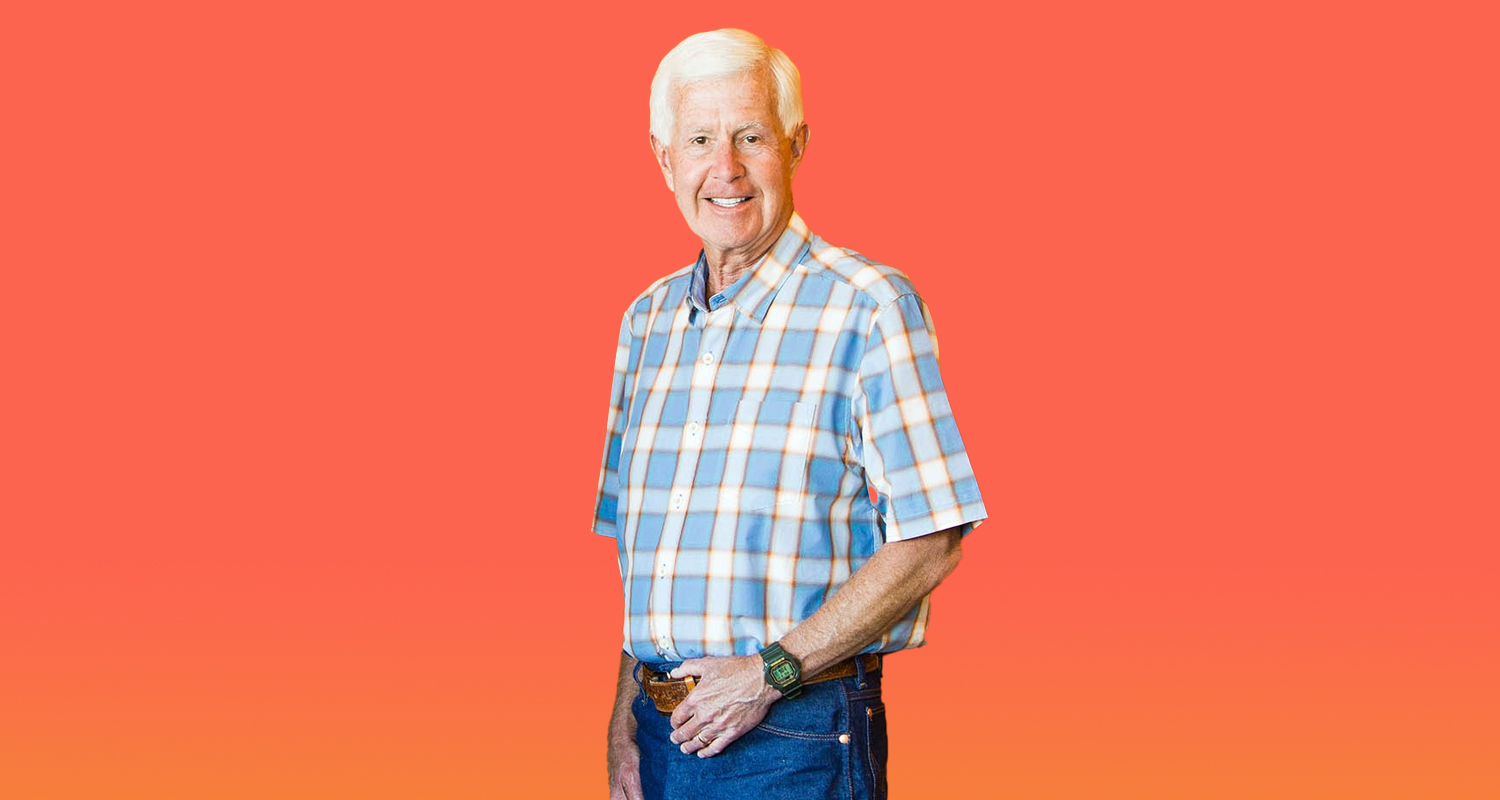

Dave Duffield keeps trying, and failing, to retire. At 84, the billionaire co-founder of HR software firms PeopleSoft and Workday is building another start-up after he became “bored silly” each time he stopped working.

“I tried to make model aeroplanes and failed, rocked away on the back porch, sort of failed at that, too,” Duffield said with a laugh from his new company’s office on the shore of Lake Tahoe in Incline Village, Nevada, US. He also played “hours and hours” of FreeCell, an online version of solitaire.

Duffield doesn’t do anything by half measures. His restless and competitive spirit drove him to start six companies, including two that he took public. He has 10 kids, two foundations and a net worth of US$15.4-billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. And those FreeCell games? He was one of the top players in the world, said his daughter Amy Zeifang.

“Maybe he played FreeCell, but he played to win it and be the best,” she said.

Now Duffield is aiming for a new milestone: completing a rare IPO hat trick and taking a third (and he claims last) company public. His latest gambit is Ridgeline, a cloud-based platform for the investment-management industry that aims to bring everything from trading to accounting to compliance under one umbrella.

Since starting Ridgeline in 2017, he’s invested about $400-million of his own money into the venture. It now has a dozen customers and is doubling that as it adds additional clients including Allen & Co, the New York investment bank. It’s eyeing an initial public offering in the next few years as it targets $1-trillion of assets on the platform and a revenue run rate of $150-million. It currently has over $200-billion on the platform; Ridgeline wouldn’t disclose its revenue.

First he’ll have to prove that his affable personality and trademark corporate culture — based on the idea that happy employees make for happy customers — can work in the cutthroat financial services industry.

Big breakout

PeopleSoft was Duffield’s big breakout company when it went public in 1992, but not his first. A Cornell University graduate who grew up in Ho-Ho-Kus, New Jersey, US, Duffield began his career as a systems engineer at IBM. He left four years later to start his first company, which designed software for scheduling college exams, before moving to Silicon Valley in the early 1970s. There he embarked on his next two ventures, both focused on human resources and payroll.

A management clash led Duffield to sell his stock in his third company, mortgage his house and start PeopleSoft in 1987. He endeared himself to his employees by pioneering Silicon Valley’s fun office culture, from casual attire to a corporate band called the Raving Daves.

That sense of a personal relationship with his workers made it even harder on Duffield when Larry Ellison’s Oracle approached with a hostile takeover offer in 2003. PeopleSoft’s board fired its CEO and asked Duffield — who was retired for the first time — to return and lead it through a bitter fight that ended with a $10.3-billion deal in December 2004.

TCS | Scott Gibson on his new role as Pragma CEO

A month later, Oracle cut 5 000 of PeopleSoft’s 11 000 employees, a turning point in Duffield’s career that he’s called the worst moment of his life.

He was “exhausted” but rather than easing back into retirement, he went to meet his former co-worker Aneel Bhusri at a diner on the California side of Lake Tahoe. Inspired by what Marc Benioff was doing with Salesforce and the cloud, they started Workday in 2005 — risking the wrath of PeopleSoft’s new owner, who suddenly faced fresh competition.

“I give Larry credit for not suing us, because that would have been a very easy thing to do,” Duffield said. “If nothing else, he could have slowed us down or forced us out of business, but he didn’t.”

Oracle didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Ellison’s hall pass gave Workday the room to grow into a $64-billion company, where Duffield remains the largest individual shareholder with a $10.6-billion stake, according to Bloomberg’s wealth index. He brought his “happy customer, happy employee” approach to his new venture and bought shares of every one of its publicly traded customers — what he called the Workday 100. (He claims it outperformed the Dow Jones Industrial Average.)

“We didn’t go overboard trying to be profitable,” he said. “We earned our profitability from having our employees be happy working hard, loving what they do, and our customers loving what we did for them, and telling others about us.”

Duffield decided to retire as Workday’s co-CEO in 2014. He and his wife had adopted their 10th and last child, and he wanted to return to Incline Village so their daughter could go to the school that he helped start in the community. But, despite remaining on the Workday board until 2022, he found himself bored once again.

“FreeCell wasn’t as prominent, but still prominent,” he joked.

To no one’s surprise, Duffield decided to go back to work. He enlisted Jack Lynch, a former IBM employee who he met at a hotel bar in Hawaii, to brainstorm ideas. The leading contender: to challenge the dominance of healthcare software firm Epic Systems with a new billing tool.

That was promptly scrapped in a pitch meeting with Allen & Co MDs Ashok Chachra and George Tenet, the former director of the Central Intelligence Agency.

Fitting capstone

“Ashok literally gets up and says something to the effect of, ‘That is total bullshit. That is the worst thing you could ever do,’” Duffield said.

Chachra later admitted he “was really blunt”, telling them that it was already a crowded field and would take years just to catch up technologically to where Epic and others were. It wasn’t a fitting capstone for Duffield’s career, he said.

Asked what he would do instead, Chachra outlined an investment industry solution with trading, accounting and CRM all built into one platform. The idea was that at every level, from the average US household to institutional investors, there’s no system of record that provides full transparency and accountability in one place.

Read: SAP staff morale plunges

And if Duffield built it, Chachra told him Allen & Co would be his first customer. In fact, it became Ridgeline’s 11th, with Tenet joining the startup’s board in 2021.

Peter Heckmann, an analyst at DA Davidson, sees an opportunity for Ridgeline to get to hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue. The investment management industry is lagging technologically but starting to see a few breakthrough start-ups challenging large incumbents like SS&C Advent, Heckmann said. He pointed to Clearwater Analytics Holdings, a competitor that’s more focused on the insurance industry, which reported revenue of $368-million last year.

Duffield’s son Mike, who’s vice president of sales for Ridgeline, thinks his dad ultimately found the right niche in an industry with pent-up demand for better technology. However, he acknowledged it’s been challenging to convince investment firms to make the leap.

Duffield’s son Mike, who’s vice president of sales for Ridgeline, thinks his dad ultimately found the right niche in an industry with pent-up demand for better technology. However, he acknowledged it’s been challenging to convince investment firms to make the leap.

“It’s open-heart surgery on their business systems and no one wants to run towards that,” said Mike Duffield, 54, who previously worked for his father at PeopleSoft and Workday. “But ultimately, it’s better for them long term.”

To convince them, Duffield turned to Dave Blair, a 28-year veteran of SS&C Advent who brought the industry knowledge to Duffield’s vision. In May, Blair completed a multiyear transition to become sole CEO. Duffield will remain the company’s chairman.

Blair, 57, said there’s tremendous pressure to get it right when dealing with trades or money transfers. Add in new artificial intelligence features, which Ridgeline is currently building, and the scepticism — and potential payoff — increase.

After some early missteps, starting with investors whose portfolios were too niche and complicated, Ridgeline now supports half a dozen asset classes from equities and ETFs to bonds. It currently has 400 employees and has opened additional offices in New York, the San Francisco Bay area and Reno, Nevada, as it races to $1-trillion in assets on the platform.

“If we add one basis point of efficiency, that’s $100-million that goes back to the end investor,” Blair said. “So that efficiency — and I think we can do a lot better than one basis point — really gives us purpose.”

Too busy to be bored

Even though Duffield has once again handed over his CEO title, he claims he’s too busy with the company, his philanthropy and his family to be bored. His youngest daughter just entered high school, he has a weekly meeting with Blair and a monthly meeting with the headmaster of Lake Tahoe School, which he helped start and has donated over $25-million to. His truck — appropriately, a Honda Ridgeline — is still a fixture outside Ridgeline’s Incline Village office.

What won’t be a focus is politics, despite a $1-million donation to Donald Trump in 2020.

“I’m not sure I would have done that again, because at the time it was negative for Workday that I did that, and I’m the last guy that wants to hurt Workday,” he said. “I would rather spend my time helping create worth, in this case Ridgeline, for the benefit of the people that come after me.”

Read: Investors suddenly can’t get enough of this five-decade-old software company

Duffield’s charity work is embarking on its next chapter, too. His Maddie’s Fund foundation, which was pivotal in leading the no-kill shelter movement and best-in-class practices for animal shelters, is now working with owners to keep animals out of shelters in the first place.

The Dave & Cheryl Duffield Foundation also has a new moonshot philanthropic goal: helping solve post-traumatic stress disorder in veterans. Duffield and his wife, along with a local developer, are building out a 27-acre site in Reno for Liberty Dogs, a new foundation that will pair 200 disabled veterans a year with service dogs.

His foundations will inherit his wealth when he and his wife die, and his children say they will continue to honour his wishes in their work. Reflecting on their dad’s legacy, his children Amy and Mike point to what he’s created for other people, from employees at his start-ups to his barber, an early investor in PeopleSoft.

On a Friday in August, Duffield and his wife sat down for dinner at a local restaurant they co-own. His net worth had risen $1.2-billion that day as Workday shares jumped 12% following a positive earnings report. When he walked in, the restaurant owner came over and excitedly told him that he’d made $17 000 that day having invested in the company too. Dinner, it would turn out, was on the house. — Biz Carson, (c) 2024 Bloomberg LP