“Ideas so simple,” reads a cartoon on an elevator door, “that they feel like the completion of a thought,” continues its twin. Similar doodles adorn the walls of HTC’s headquarters in Taoyuan, near Taipei, and business cards carried by the smartphone-maker’s staff. John Wang, the chief marketing officer, lays out a set of four: concentric circles with a smiley in the middle, denoting a focus on the customer; an arrow from A to B, for simplicity; a magnet, for “hidden power”; and a parcel, for “pleasant surprises”.

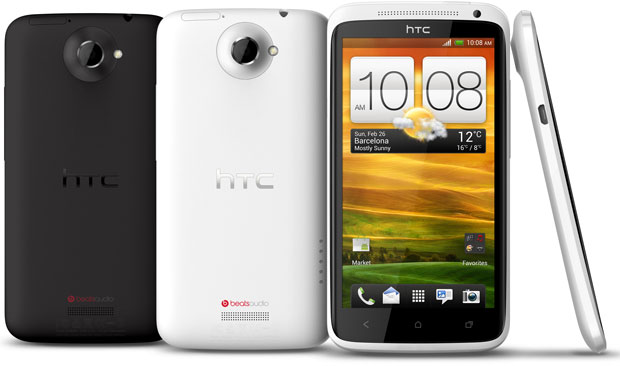

Meaning what, in practice? Wang shows off the camera in HTC’s new range of smartphones, the One series, which goes on sale this month. It is super-fast, focuses and shoots in a fifth of a second, takes photos in rapid succession and does away with cumbersome switching between stills and video: you can take snaps while filming or replaying. The engineering is hard, but hidden. The camera is easy to use. It is a pleasant surprise.

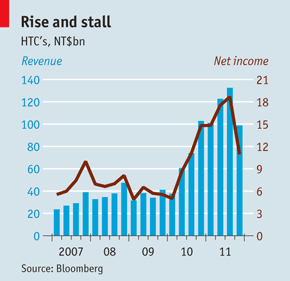

Last year, however, HTC produced an unpleasant one: sales and profits plummeted in the fourth quarter (see chart). In the first two months of 2012, revenue was a staggering 45% down on last year. In February, Winston Yung, the chief financial officer, admitted that HTC had “dropped the ball”. Analysts mused that last year’s products were not its best: perhaps fast growth caused a loss of concentration. And the competition, from Apple’s iPhone 4S and Samsung’s Galaxy S2, was ferocious.

Mobile-phone brands can flower and fade quickly. On 29 March, Research In Motion, the Canadian maker of the BlackBerry, the latest to wilt, announced a quarterly loss, the departure of senior executives and a “comprehensive review”.

No firm has bloomed as suddenly as HTC. Until 2006, when it started selling phones under its own name, it had no brand to speak of. Yet now only Apple and Samsung sell more “high-end” smartphones (costing US$300 or more). In America, it sold more smartphones than anybody else in the third quarter of 2011, according to Canalys, a research firm.

No firm has bloomed as suddenly as HTC. Until 2006, when it started selling phones under its own name, it had no brand to speak of. Yet now only Apple and Samsung sell more “high-end” smartphones (costing US$300 or more). In America, it sold more smartphones than anybody else in the third quarter of 2011, according to Canalys, a research firm.

This month, two things will happen that HTC hopes will revive it. It will start selling a new crop of phones and step up its efforts in China, a market it entered only in July 2010. IDC, a research firm, says China will become the world’s biggest market for smartphones this year. Others reckon it already is.

Founded in 1997, HTC began as one of many Taiwanese firms that design and make things that are sold under others’ brands — in its case, brands belonging to mobile-phone operators and computer-makers. In 2000, it produced the iPAQ, a personal digital assistant, for Compaq, a firm bought by Hewlett-Packard in 2002. HTC’s original name was High Tech Computer, which is as anonymous as it gets.

It won a reputation for excellent engineering. But it wanted more, and began to invest more in innovation before eventually creating its own brand. It set up a unit called Magic Labs, which was charged with coming up with lots of ideas, even if most were quickly discarded. (Wang was its “chief innovation wizard”. He still has a few of those business cards, too.) From this came, notably, the HTC Touch, a touch-screen device that appeared in 2007, at about the same time as Apple’s first iPhone. Wang admits to feeling “terrible” when the iPhone appeared, but he says he soon felt “at ease”. Because “HTC had a very weak brand back then”, take-up of the new phones would have been slower had Apple not made touch-screens cool.

Spectacular growth came hand in hand with that of Android, Google’s mobile operating system. HTC latched on to this early, making the first Android smartphones, despite an earlier tie-up with Microsoft. Like everyone else, it has caught shrapnel in the patent wars. In December, America’s International Trade Commission ruled that some HTC devices had infringed an Apple patent and should be banned from America from 19 April. HTC says a redesign will deal with the objection.

Patent wars may not have halted it, but it has stumbled nonetheless. Pierre Ferragu of Sanford C Bernstein, an investment bank, links its decline to the “tyranny of the flagship”: the tendency for top-of-the-range phones to scoop a disproportionate share of the market. Ferragu reckons that in the fourth quarter of 2011, 30% of volume, 52% of sales and 87% of operating profits were accounted for by iPhones and Samsung’s Galaxy S2 alone. He expects these ratios to fall and thinks that HTC is best placed to gain.

Yung promised that growth would resume when new products appeared. There are reasons to be cheerful. The One phones were well received when HTC showed them off at Mobile World Congress, an industry jamboree, in Barcelona in February. Deals with 140 operators and distributors around the world should help get them into consumers’ hands.

In China, explains Ray Yam, the head of HTC’s business there, the company started later than in richer parts of the word largely because the country’s mobile infrastructure was iffy. These days 10-15% of users have 3G, a figure expected to rise rapidly; and more people have access to Wi-Fi, in public places if not at home. HTC has taken about 10% of the market for smartphones costing more than 2 000 yuan (about $300). It is time for a further push.

So HTC is launching its first national marketing campaign. It will also open many more “shops in shops” — booths run by manufacturers in electronics stores in which they jostle for custom. HTC has 2 300 so far; Yam expects there to be 4 000 by the end of the year and 6 000-7 000 eventually. (He reckons Apple has 3 500 and that Nokia and Samsung have 9 000 each.) HTC is also introducing phones tailored for the Chinese market. Last month, the Triumph, the first phone in China with the newest version of Windows, went on sale. Also coming is the Desire, which has the latest incarnation of Android and can switch between operators with incompatible standards.

Here’s to China

“This year is a very important one for HTC,” says Yan Siqing, chief operating officer of China Telling Telecom, which distributes around 15% of the country’s mobile phones. Yan, whose firm works mainly with global brands, including HTC, says HTC grew rapidly in China last year, despite its late start, because it provided a “good user experience”. People know the brand and like the phones. “Its main competitor in [China] is Samsung. Apple is higher up and for now there’s no way to compete with them.” Nokia is another strong brand but its Windows phone is still new. That gives HTC “time for growth”.

HTC has a good chance of bouncing back this year. Ben Wood of CCS Insight, a research firm, thinks it “has pulled it back with these new products”, but he adds that the firm is only as good as its latest device. The market changes fast.

That means HTC will have to keep turning out hits. Others have seen it rise from anonymity to omnipresence and want to follow: Huawei and ZTE, two Chinese hopefuls, are far behind but hungry. HTC cannot yet rely on other sources of income: its tablet, the Flyer, has not yet flown. Apple, Samsung and the rest have alternative means of support. They also have many more billions to throw at marketing. HTC prefers to let its products do the talking. It seems confident that people will listen. — (c) 2012 The Economist![]()