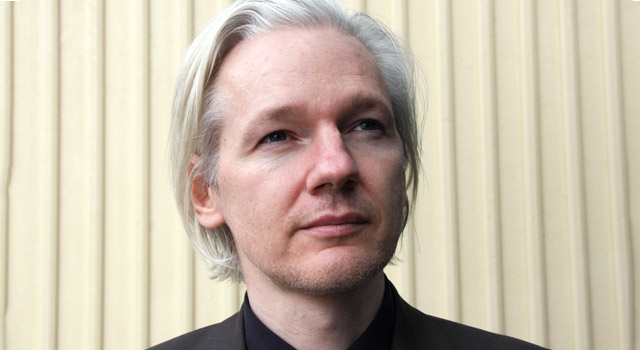

You almost have to feel sorry for Julian Assange. Shut in at the Ecuadorean Embassy in London without access to sunlight, the founder of WikiLeaks is reduced to self-parody these days.

Here is a man dedicated to radical transparency, yet he refuses to go to Sweden despite an arrest warrant in connection with allegations of sexual assault. His organisation retweets the president-elect who once called for him to be put to death. He spreads the innuendo that Seth Rich, a Democratic National Committee staffer, was murdered this summer because he was the real source of the e-mails WikiLeaks published in the run-up to November’s election. And now he tells Fox News’s Sean Hannity that it’s the US media that is deeply dishonest.

This is the proper context to evaluate Assange’s claim, repeated by Donald Trump and his supporters, that Russia was not the source for the e-mails of leading Democrats distributed by WikiLeaks.

We all know that the US intelligence community is standing by its judgment that Russia hacked the Democrats’ e-mails and distributed them to influence the election. And while it’s worrisome that Trump would dismiss this judgment out of hand, this also misses the main point. Sometimes the spies get it wrong, like the “slam-dunk” conclusion that Saddam Hussein was concealing Iraqi weapons of mass destruction.

The real issue is Assange. The founder of WikiLeaks has a history of saying paranoid nonsense. This is particularly true of Assange’s view of Hillary Clinton. His delusions have led him to justify the interference in our elections as an act of holding his nemesis accountable to the public.

Bill Keller, the former New York Times executive editor, captured Assange’s penchant for dark fantasy in a 2011 essay that described him casually telling a group of journalists from The Guardian that former Stasi agents were destroying East German archives of the secret police. A German reporter from Der Spiegel, John Goetz, was incredulous. “That’s utter nonsense, he said. Some former Stasi personnel were hired as security guards in the office, but the records were well protected,” Keller recounts him as saying.

In this sense, WikiLeaks’ promotion of the John Grishamesque yarn that Seth Rich was murdered on orders from Hillary Clinton’s network is in keeping with a pattern. Both Rich’s family and the Washington police have dismissed this as a conspiracy theory. That, however, did not stop WikiLeaks from raising a US$20 000 reward to find his “real” killers.

Add to this Assange’s approach to Russia. It’s well known that his short-lived talk show, which once aired a respectful interview with the leader of the Lebanese terrorist group Hezbollah, was distributed by Russian state television. WikiLeaks has also never published sensitive documents from Russian government sources comparable to the US state department cables it began publishing in 2010, or the e-mails of leading Democrats last year.

When an Italian journalist asked him last month why WikiLeaks hasn’t published the Kremlin’s secrets, Assange’s answer was telling. “In Russia, there are many vibrant publications, online blogs, and Kremlin critics such as [Alexey] Navalny are part of that spectrum,” he said. “There are also newspapers like Novaya Gazeta, in which different parts of society in Moscow are permitted to critique each other and it is tolerated, generally, because it isn’t a big TV channel that might have a mass popular effect, its audience is educated people in Moscow. So my interpretation is that in Russia there are competitors to WikiLeaks, and no WikiLeaks staff speak Russian, so for a strong culture which has its own language, you have to be seen as a local player.”

This is bizarre for a few reasons. To start, Assange’s description of the press environment in Russia has a curious omission. Why no mention of the journalists and opposition figures who have been killed or forced into exile? Assange gives the impression that the Russian government is just as vulnerable to mass disclosures of its secrets as the US government has been. That’s absurd, even if it’s also true that some oppositional press is tolerated there.

Also, WikiLeaks once did have a Russian-speaking associate. His name is Yisrael Shamir, and according to former WikiLeaks staffer James Ball, he worked closely with the organisation when it began distributing the US state department cables. Shamir is a supporter of Vladimir Putin.

This is all a pity. A decade ago, when Assange founded WikiLeaks, it was a very different organisation. As Raffi Khatchadourian reported in a 2010 New Yorker profile, Assange told potential collaborators in 2006: “Our primary targets are those highly oppressive regimes in China, Russia and Central Eurasia, but we also expect to be of assistance to those in the West who wish to reveal illegal or immoral behavior in their own governments and corporations.”

For a while, WikiLeaks followed this creed. The first document published, but not verified, was an internal memo purporting to show how Somalia’s Islamic Courts Union intended to murder members of the transitional government there. It published the e-mails of University of East Anglia climate scientists discussing manipulation of climate change data. In its early years, WikiLeaks published information damaging to the US as well. But no government or entity or political side appeared to be immune from the organisation’s anonymous whistle-blowers.

Today, WikiLeaks’s actions discredit its original mission. Does anyone believe Assange when he darkly implies that he received the Democratic National Committee e-mails from a whistle-blower? Even if you aren’t persuaded that Russia was behind it, there is a preponderance of public evidence that the e-mail account of Hillary Clinton’s campaign chairman John Podesta was hacked, such as the e-mail that asked him to give his password in a phishing scam. Assange himself is not even sticking to his old story: he told Hannity that a 14-year-old could have hacked Podesta’s e-mails. Good to know.

In short, the founder of a site meant to expose the falsehoods of governments and large institutions has been gaslighting us. Just look at the WikiLeaks statement on the e-mails right before the election. “To withhold the publication of such information until after the election would have been to favour one of the candidates above the public’s right to know,” it said.

That’s precious. WikiLeaks did favour a candidate in the election simply by publishing the e-mails. And the candidate it aided, Donald Trump, is so hostile to the public’s right know that he won’t even release his tax returns. In two weeks, he will be in charge of an intelligence community that asserts with high confidence the e-mails WikiLeaks made public were stolen by Russian government hackers. Assange, of course, denies it, and Trump seems to believe him. Sad! — (c) 2017 Bloomberg LP

- Eli Lake is a Bloomberg View columnist. He was the senior national security correspondent for the Daily Beast and covered national security and intelligence for The Washington Times, The New York Sun and UPI