ICQ, a once-dominant instant messaging app developed by Israeli company Mirabilis in 1996, is shutting down for good after 28 years.

ICQ, a once-dominant instant messaging app developed by Israeli company Mirabilis in 1996, is shutting down for good after 28 years.

ICQ, which was acquired by America Online in 1998, and then by Russia’s Mail.ru (now VK) in 2010, was for many people of a certain age their first introduction to instant messaging on the internet.

TechCentral has a look at the history of instant messaging (IM), which goes all the way back to the very early days of computing, to the era of Beatlemania and the space race between the US and the Soviet Union.

When instant messaging kicked off in the 1960s (it wasn’t even called that back then), the idea that someone could send an AI-generated animated emoji was completely foreign. Today that’s all possible in apps like Meta Platforms’ WhatsApp, which is used by more than three billion people around the world. (Three billion was the world’s total population in 1960.)

Back then, however, people didn’t carry high-powered computers in their pockets. Instead, those lucky enough to have access sat at a green-screen terminal sharing the resources of a large mainframe computer costing millions of dollars. They could communicate with each other and get notifications about system operations, like when another user was printing (and hogging limited computing resources) – and not much else.

The arrival of the early internet in the 1970s sparked the first big evolution in IM applications, allowing people using different computers to hold a conversation, so long as they were connected to the same network.

Talkomatic

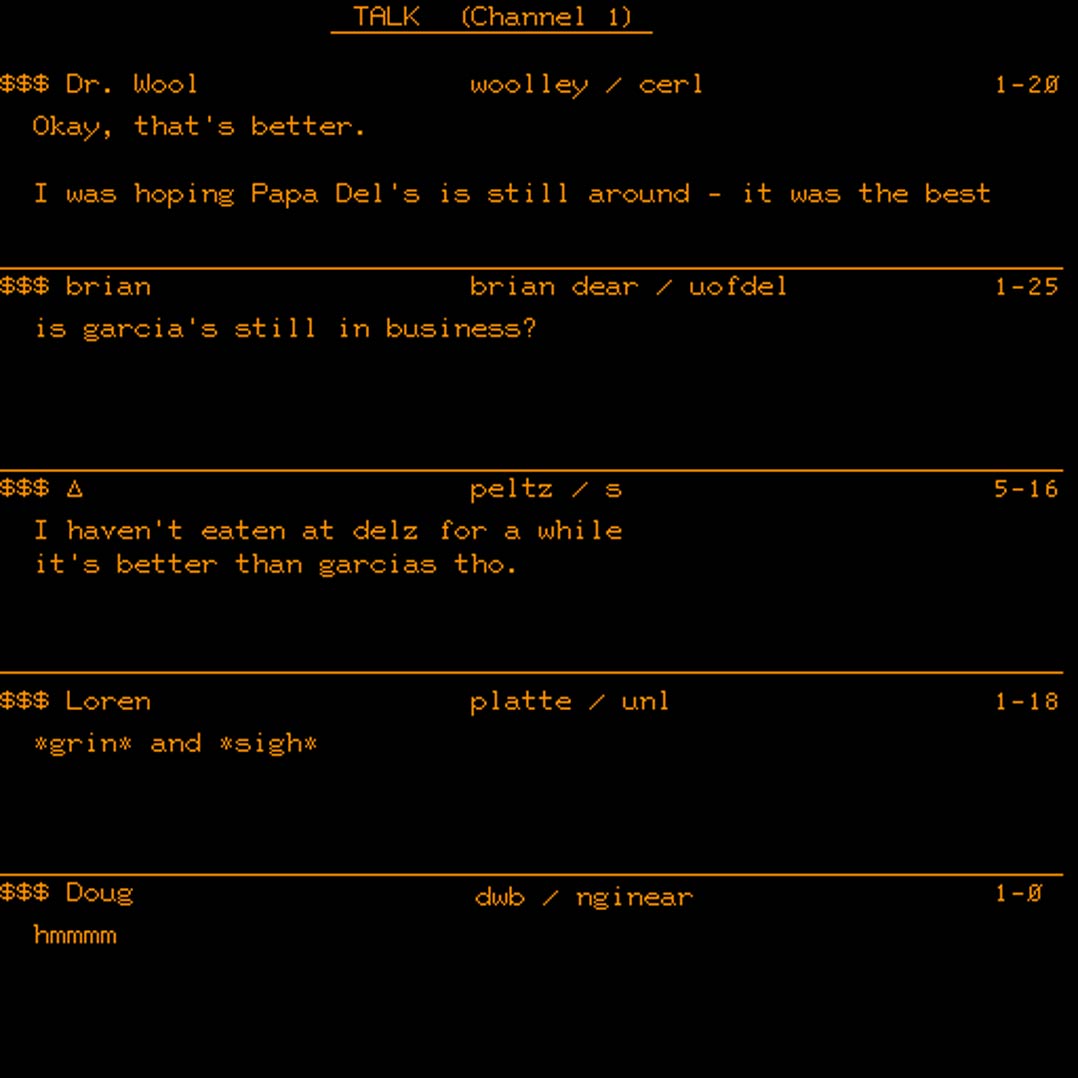

The first online chat system, called Talkomatic, was developed in 1973 for the Plato computer system by Doug Brown and David R Wooley at the University of Illinois. Up to five people could chat simultaneously using Talkomatic, with each participant “owning” a portion of the screen. The chat looked more like the interaction of five different bulletin boards each broadcasting their signal to the rest of the group.

The next big revolution in IM came in 1988 with the creation of internet relay chat (IRC). IRC allowed for platforms with multiple chat rooms, or channels, based on user interests – anything from gaming and outdoor to astronomy. It was all mostly text-based, prior to the widespread adoption of graphical user interfaces (GUIs) in the 1990s.

Advancements in graphics led to the development of GUI-based messaging clients for desktop PCs. PowWow, ICQ and AOL Instant Messenger (AIM) dominated this era of IM. But, towards the end of the decade, the market became fiercely competitive, with a range of software and internet companies muscling in: Excite, Microsoft’s MSN, Ubique and Yahoo.

Read: It’s official: BBM is dead

The proliferation of multiple, incompatible chat clients meant users had to run more than one client to keep up with friends, family and colleagues, especially if those people lived in different countries.

To solve this problem, Mark Spencer of Auburn University created Pidgin in 1998, which made cross-platform IM popular. Instead of requiring unique software to connect with each platform, Pidgin amalgamated them in one platform.

…article continues below…

Jabber, created in 2000, used open-source standards to overcome the interoperability problem. Jabber’s protocol was later standardised as Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol (XMPP).

Video chat was starting to gain traction by the early 2000s, with the launch of Skype in 2003 signifying an uptick in the sophistication of chat clients. But desktop computing was about to face a new challenger as cellphones would soon become powerful and sophisticated enough to run applications previously too compute intensive.

By the mid-2000s, the mobile revolution was in full swing and an arms race was on between tech companies to build the chat application for the emerging mobile era. In South Africa, Mxit – cleverly engineered to run on basic feature phones – dominated the market for several years. But the device landscape was already changing quickly.

First, BlackBerry emerged as a hot-ticket item among South African consumers – a phenomenon that was replicated in a few markets around the world, including Indonesia. Demand soared as operators offered the uncapped BlackBerry Internet Service (BIS), making messaging using BlackBerry Messenger (BBM) virtually free.

BlackBerry’s rise was short-lived, however, as the smartphone revolution – started in 2007 with the introduction of the first iPhone from Apple – shifted the market dynamics again.

Ultimately, though, Apple wasn’t successful in capturing the global market with an IM tool of its own: rather, WhatsApp Messenger, later acquired by Facebook (now Meta), emerged from a crowded field as the most popular smartphone-based IM app in most countries, including South Africa.

WhatsApp’s dominance

WhatsApp brought with it a value proposition so compelling that it overcame any of the network effects that Mxit and BBM had amassed in the local market: a high-quality, asynchronous chat experience that was also cheap and accessible on any kind of device. A decision by the mobile operators to end the cheap BIS party also contributed to BBM’s demise.

Today, WhatsApp still dominates in South Africa and many markets around the world – and nothing looks likely to knock it off its perch anytime soon. However, ICQ, BBM and even Mxit looked unstoppable at their peak, only to lose the interest of fickle users when something more compelling came along. – © 2024 NewsCentral Media