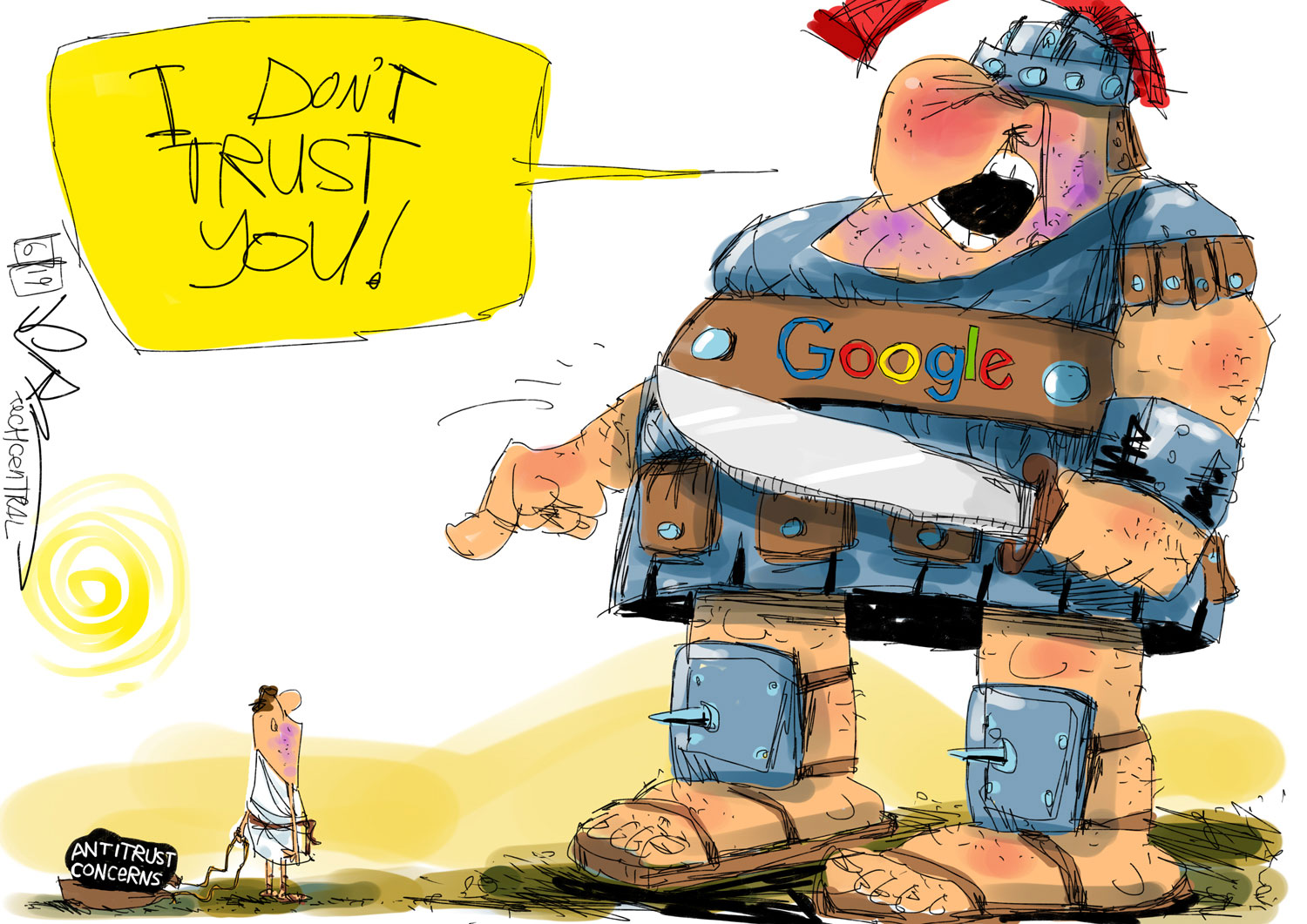

The future of the tech industry was once decided by messianic entrepreneurs (assisted by venture capitalists and assorted Silicon Valley boosters) pumping out their sermons to rapt crowds in cavernous arenas. Today, it’s the fustier crew of competition regulators and policy wonks — more commonly spotted in carpeted conference rooms — who appear to have seized the pulpit.

The future of the tech industry was once decided by messianic entrepreneurs (assisted by venture capitalists and assorted Silicon Valley boosters) pumping out their sermons to rapt crowds in cavernous arenas. Today, it’s the fustier crew of competition regulators and policy wonks — more commonly spotted in carpeted conference rooms — who appear to have seized the pulpit.

Investors in Apple, Facebook and Alphabet will no doubt testify to this shift in power after the threat of US antitrust action caused their shares to fall at the start of this week. (Apple’s have rallied slightly.)

There was certainly a great show of purpose from the attendees at an OECD trust-buster gathering that I attended in Paris on Monday, helped no doubt by the Americans finally starting to follow Europe’s lead in tackling the tech giants’ monopolistic tendencies. Margrethe Vestager, the EU’s top competition official, lined up with officials from the US department of justice and Federal Trade Commission, as well as top regulators from Britain, France and Germany, to offer pointers about what lies in store for the industry.

While there’s still plenty of tension between officials on both sides of the Atlantic, the overall picture was of a regulatory class that’s determined to make up for lost time. Even in Europe, there’s a sense of having left too much in the hands of the market for too long. Vestager, looking back over her five-year tenure that resulted in three fines against Google, admitted: “We could have been faster.”

Regret is a powerful thing, especially when the political pressure to act is rising. The example of Instagram was frequently referred to as something that flew under everyone’s radar: its sale to Facebook for US$1-billion was waved through in 2012, largely because it had a handful of staff, earned no revenue and was to be kept at arm’s length. The fact that Instagram is now a behemoth in its own right has woken up regulators to the need to take a tougher line on big tech gobbling up promising start-ups.

Objections

Instagram had 30 million users at the time Facebook acquired it. Today, it has more than a billion. Crucially, Instagram shares vast amounts of user data with its parent network, a practice that drew objections from German regulators earlier this year. Back in 2012, though, there were few concerns: UK competition watchdogs wrote at the time that most third parties “did not believe that photo apps are attractive to advertisers”, citing the fact that “limited” user data was captured.

In fairness to Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, it’s not his fault that he had a more acute grasp of Instagram’s potential, but this shouldn’t stop the market cops from trying to up their game to avoid even more social media power ending up in one man’s hands.

How many other Instagrams have flown under the radar? It’s hard to say. Andrea Coscelli, head of the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority, estimates that Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google and Microsoft have together bought close to 250 companies in the past five years. For every big-budget acquisition like Facebook’s WhatsApp deal, there are several like “tbh”, a teen social network bought by Zuckerberg in 2017 and quietly shut down afterwards.

There’s a feeling among regulators that start-ups aren’t really being given the chance to grow and compete — they get bought as soon as they enter Big Tech’s “kill zone” (where promising potential rivals are simply taken out). Expect more of a push to tackle this practice, such as by lowering the burden of evidence required to identify potential anticompetitive harm from a takeover. Ariel Ezrachi, professor of competition law at Oxford University, says officials are becoming alert to “the cost of doing nothing”.

So, should Google, Facebook and the rest expect a concerted antitrust crackdown from the US to match the EU’s? Maybe, though at the OECD meeting there wasn’t much appetite for aggressive action like break-ups. Both the DOJ official Andrew Finch and the FTC’s Noah Phillips were at pains to stress that size wasn’t bad in itself; but “big, behaving badly” is a problem, Finch said. As such, hefty fines are a more likely outcome.

While there are plenty of other American voices calling for a revival of the kind of monopoly dismantling seen during the days of John D Rockefeller, Finch said the current era felt less like the Gilded Age and more like the 1990s and 2000s, when companies used patents to stunt the growth of their rivals. “These moments tend to work themselves out,” he told me. Not exactly the kind of tub-thumping in which Elizabeth Warren might engage.

So the smart money’s still on Europe taking the more adventurous and aggressive antitrust measures. But there’s no ignoring the shift on both sides of the Atlantic. People want tougher rules, and they will come. — By Lionel Laurent, (c) 2019 Bloomberg LP