As you might have seen, the networks are at it again, on a drive to get the government to regulate Web services, which these network operators like to call “over-the-top” (OTT) providers.

As you might have seen, the networks are at it again, on a drive to get the government to regulate Web services, which these network operators like to call “over-the-top” (OTT) providers.

Regulating Internet services will have a huge ripple effect throughout the economy. I don’t even want to start thinking about how badly this could be implemented.

How on Earth would such regulation even be managed? Can you imagine Facebook opening offices in every city or appointing officials in small towns to do Rica just so South Africans can talk to each other online?

I can’t see this happening, though. It is counterintuitive and anti-Internet to add such labour-intensive processes. If Vodacom and MTN have their way and companies such as Facebook and Google are somehow forced to add complex and unnecessary red tape to the sign up and account-creation process, all that will happen is they will pull out of the country.

Fighting for regulation instead of innovation

While organisations like Digital Village, Project Isizwe and the Western Cape government are making an effort to get more people online and bring communication costs down, companies like Vodacom and MTN are publicly making an effort here to screw the South African consumer.

These big companies are pleading poverty while the CEO of Vodacom was paid R10,9m in 2015 and the CEO of MTN R28,1m in 2014. Who are they trying to fool?

They sell bandwidth to consumers and then, if you don’t use it within a certain amount of time, you lose it. Imagine buying a hamburger, but because you don’t eat it fast enough, the restaurant throws it away. There is no way we would accept that from anyone in retail, so why on Earth is it acceptable from a cellular service provider?

Meanwhile, forward-thinking network operator Cell C is embracing OTT players and says regulation could hurt the industry. That’s stating the obvious.

I’ve been a Vodacom customer for going on 18 years now and I’ve generally been happy with the service, even if I haven’t been happy with the pricing. I have, however, reached the point where I feel we need to start threatening to cancel our contracts and moving to operators like Cell C that have embraced the future.

Networks like MTN and Vodacom need to realise that they are nothing more than utilities. The only value they have to offer us in the long term is faster connectivity and wider network coverage. There is, however, nothing stopping them from investing in Internet start-ups or creating their own OTT services.

Why not rather be productive and contribute to society by incentivising innovation or establishing and running accelerators or incubators? They could even create investment vehicles to push our economy forward, in new directions, leveraging their core network and embracing new technologies instead of spending time, effort and money on slowing down progress with legal or regulatory proceedings and attacking companies offering services that benefit the community and economy.

Let’s debunk some myths

Service providers make some blanket claims that indicate they don’t understand how the Internet or hosting business works. Worse, it seems that the CEOs of these companies that make the claims don’t understand how the billing systems work at their own companies.

Part of what is so infuriating about this whole situation and some of the accusations being thrown around is that both Vodacom and MTN are also commercial Internet service providers, operating data centres, home to what they themselves refer to as OTTs. As a result of hosting and bandwidth utilisation being a source of revenue for network operators, they should know that anyone operating a cloud service (an OTT service) pays for hosting and bandwidth utilisation.

Myth 1: OTT operators are ‘free riders’

Every cat picture and meme you look at on Facebook costs both you and Facebook money to transmit over the Internet. The same goes for watching videos on YouTube and Netflix.

Every website and Web service pays to stay online. Companies such as Facebook, Twitter, Google, Microsoft and Apple pay enormous amounts of money to run servers in countries around the world.

They either rent data centre space or set up their own data centres. They need to pay to connect to Internet service providers and either pay for bandwidth used or for dedicated bandwidth/pipe.

Think of it this way. At home, you can either have capped or uncapped ADSL. If you have capped ADSL, you pay for data used; if you have uncapped ADSL, you pay for the size/speed of your data pipe/connection. In other words, the amount of data you can transmit per second.

Uncapped connections usually come with a fair-usage policy, which sets an upper limit on how much bandwidth you may transmit either via upload or download during a 30-day period before being throttled. These same concepts apply to the tech giants, but on a massively different scale. Instead of needing to worry about megabytes, they’re working with terabytes and petabytes. All of this costs real money.

Myth 2: OTT services are being used for free

The cheek and audacity of network operators to complain that accessing OTT services is free is unbelievable.

Users — also known as paying customers — access the Internet either through purchasing data bundles from Internet service providers or mobile networks or paying for network access in the form of a monthly subscription. Once on the network, users can access hosted websites and services, all of which use bandwidth for which they have paid.

Below I outline some differences between the traditional and modern (Internet) engagement and billing models.

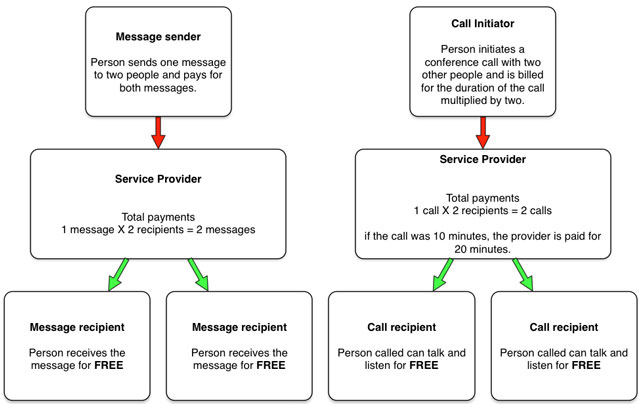

In the old model, the person initiating the phone call or sending the message is the only one who pays for the communication¹.

Take the “please call me” service.

A “please call me” allows someone without airtime to send a free message to someone else (presumably with airtime) to call them back. The reason this works and is viable is because the person who initiates the call pays for it so the person being called, in this case the person who sent the “please call me”, does not need to have any airtime as their participation in the conversation is free. They could both listen and speak without incurring any cost.

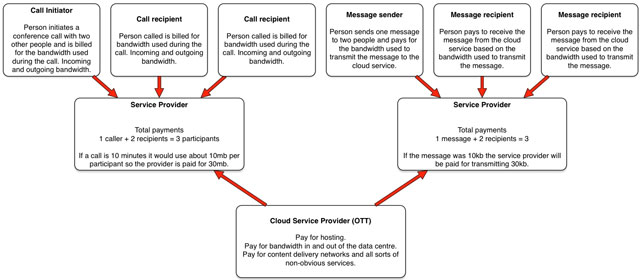

There is a big difference in how Internet-based services work compared to the traditional model².

In the modern Internet world, the networks being operated by the telecommunications companies, whether they be cellular or fixed line, provide a data conduit through which devices can communicate with each other. All devices on the big interconnected network, also referred to as the Internet, pay to participate and pay for data traffic in both directions.

With this in mind, any OTT operator doing their job properly will be using compression and efficient encoding to reduce the bandwidth being used by their service as it costs them money to operate. This leads to less strain on the network and smaller data packages being sent between devices. As a result of this, modern, Internet-based communication is more efficient and generally uses the least possible amount of data required to get the job done. This is good for everyone, even the traditional Internet service providers, as it reduces the load on the networks. It might not result in a surge in data usage (and revenue) upfront, but in the long term it results in faster Internet adoption and more users spending money to get online and do business online.

Due to both directions of traffic being billable, all parties pay to be part of a conversation. Whether it is a voice-over-Internet protocol call or a group chat via instant messaging, users pay to both send (upload) and receive (download) data. This means the more people participating in a conversation, the more bandwidth is being invoiced, even if only one person is sending the messages or speaking.

Regulation will affect everyone

Tell your friends and your family. Help them understand the far-reaching impact should Vodacom and MTN get their way. This is an issue that will affect us all. The definition of OTT is vague and could eventually be twisted and applied to this very website you’re reading.

- Calls made to networks, other than the user’s home network, are handled through interconnection, which is a complex issue on its own.

- This only covers the high-level concepts; the billing structure is actually more complex. I’m just trying to illustrate that it’s a multi-payer situation now and that same packet of data is being paid for multiple times by different parties. There are other more complex issues such as peering which this Ars Technica article covers quite nicely.

- Nathan Jeffery is a technology strategist who invests in and consults for technology start-ups on product development and infrastructure. He is founder and CEO of software development company MyEcommerce, co-founder and director of the Garden Route ICT Incubator, and chief product officer for construction project management software-as-a-service company Hlalani IQ